Daniel Abiva Hunt

Before Our Time on This Earth Ends

“My name is Allen Carl. I am eighty-two years young, and I write about geriatric sex.”

That was how he introduced himself, with a gleam in his eye as he watched for the inevitable shock on his listener’s face.

“Friends call me Carl,” he said. “Wife calls me King.”

This introduction took place many years ago, when I was a younger man, at a writing conference on the Emerald Coast of Florida, a place known for its pristine beaches and charming coastal towns. Carl and I were the first to arrive at the assembly hall, our home base for the week. The hall was a repurposed school building and featured a grassy courtyard and a stone church with a white marble clock tower whose hands were stuck on noon.

I introduced myself.

“Daniel Abiva Hunt,” Carl said, studying me. “Why does that name sound familiar? Are you famous?”

“No,” I said, laughing off the last question. “You probably saw it on the conference email list. We’re roommates.”

“Ah.” Carl then leaned in close. “Just a heads-up, I’m recovering from a nasty bout of shingles. Not contagious anymore, thank God. But let me tell you, I’m looking forward to peeling this shirt off and soaking in that hot tub.”

The conference directors then bustled in with welcome folders and lanyards with nametags. Carl picked up his materials with the confidence of familiarity. “I was here last year,” he told me. “Had a great time, but I haven’t written a new word since.”

“Oh?” I said. I was not sure how to respond, and I was distracted. Across the hall, I spotted a volunteer—a poet a few years younger than me. Our eyes met briefly. She was arranging pamphlets on a side table with excerpts of verses that spoke of time and memory.

“Yep,” Carl said, pulling my focus away from the mysterious poet. “I’ve been too busy applying what I learned—revising, slowing down, staying in scenes longer, and being deliberate about point of view shifts. They have to really count, you know?”

I asked him about his book, a question I knew writers either relished or took as personal insult.

“It’s about old folks navigating sex before their time on this Earth ends,” he said.

As we wrapped up registration, Carl drove us to our house. His ocean-blue Bronco was equipped with a rooftop camper. He said the vehicle was suited for sleeping under the stars. Despite living only thirty minutes away in Panama City, he preferred staying on-site at the writing conference, blurring the lines between reality and imagination.

Carl navigated the confusing roads of the coastal town. We circled the main square—encased in boutique shops and bustling food stands—multiple times. He finally accepted my offer to use GPS after driving the wrong direction down a one-way street. The secluded trailer was tucked away under a canopy of moss-laden oaks, not quite the beachside cottage described by the conference. The setup was simple: two bedrooms, a shared bath, and a combined kitchen-living room area. We would be brushing up against one another for a week.

Carl claimed the larger bedroom. I did not protest. I assumed he had certain needs given his age. We pooled our snacks in the kitchen: his K-cups and cashews and the Hawaiian chocolates I purchased at the airport.

In the kitchen, Carl took off his shirt to reveal a crusty rash on his shoulders and back, a symptom of his recent disease. I tried not to stare at his skin, reminiscent of my own chickenpox scars from childhood. I noted to myself to keep my distance, though I found his commitment to the conference, despite his condition, admirable at the time, and I feel fortunate to have avoided shingles myself to this day, especially now that I have lived longer than Allen Carl ever did.

At that time in my life, my reason for attending writing conferences was straightforward. I had recently left a risk analyst role at a New York City bank to pursue fiction writing full time. My former job involved analyzing potential outcomes of corporate strategies—investments, economic shifts, client acquisitions—but my lifelong passion was writing, a pursuit attended to over early morning coffee and late-night Tanqueray. I was single and had no responsibilities, and I approached the craft with the same analytical rigor as my previous career, relying on detailed spreadsheets to monitor my progress. My stories had garnered some attention; I was an honorable mention in a national literary contest. This conference was an opportunity to network with industry influencers, to take the next step in my literary career.

My aim at the time was to get a book published. I had assembled a collection of short stories, exploring the lives of characters at different life stages. The stories unfolded across a fictional region called the Great Half State of South Jersey, an allegorical landscape that mirrored the fractured psychological states of the characters. The query letter I crafted described the collection as tragicomic, the characters struggling beneath the burdens of capitalism, muddled dreams, and loneliness.

I refined the pitch repeatedly, distilling it down to bookstore phraseology designed to capture an agent’s interest. Finally, after months, there was a faint glimmer of hope: someone requested the full manuscript. But after a long three-month wait, my follow-up email was met with an automated reply: the agent had not only left the agency but had abandoned the literary world entirely.

The first full day of the conference began with Carl’s alarm clock blaring at 5 AM. The morning sun pierced through the mini-blinds of our trailer. I felt the aftereffects of the welcome reception’s rosé. The evening had ended on the beach, in deep conversation with the mysterious poet I had noticed at registration. Our parting was marked by the promise of deeper discussions to come.

An incessant dinging from the kitchen, like a stock market bell, dragged me from bed. I stepped into the living room where I discovered the source of the noise: Carl’s computer. There, he sat watching CNBC, while his inbox chimed with each new email. Carl, I would learn, was still an active financial advisor.

In the kitchen, the Keurig groaned to life. Carl sat at the table shirtless, skin pockmarked by sun and disease, studying a manuscript. “What do you make of the passive voice?” he asked. “Someone in my workshop commented on my use of passive voice. I’m not sure what they mean.”

I explained the concept as best I could, suggesting that the active voice makes statements more direct, whereas the passive voice obscures who is doing the action. Carl nodded. “You’re one of those literary types?” he asked.

I shrugged.

“I subscribe to a few literary journals,” he said. He named the most famous ones. “But I’ll be honest, I find the stories drag. I prefer a narrative that’s fast-paced, with high-stakes, clear conflicts, and satisfying resolutions.”

“Me too,” I lied.

The night before, the poet and I had discussed the nature of storytelling—how sometimes the beauty of a narrative lies not in plot, but in the depth of the introspection, the resonance of the voice. As I watched Carl, studying the feedback from his workshop, a nagging doubt emerged. Maybe there was something to his preference for pace and stakes that my own writing lacked.

In the kitchen, Carl meticulously annotated his manuscript. I wasn’t sure what kind of writer he was, what kind of talent he possessed. Over the years, I had seen plumbers blossom into true artists. I had seen the most promising lyricists quit for good. I assumed Carl was like most of us, still just trying to find his voice.

As we sipped our coffee, Carl interrupted the silence, launching into a story from a recent kayaking trip in Okaloosa County. He narrated the challenges of navigating the gulf at dusk and the unexpected beauty of finding shelter during a storm. The way he described the freezing rain and the refuge of a warm bathroom was actually quite compelling. “I took my clothes off and took a piss and stood under the heat of the hand dryer until the feeling in my toes returned and I stared up at the water-stained ceiling tiles and thought, the Sistine Chapel could not be more beautiful.”

“That’s a good story,” I said. “You should write it.”

He laughed. He told me he had already written it, only in the fictionalized version, the stakes were much higher, involving a life-or-death confession to adultery and a dramatic conclusion in shark-infested waters.

I did not tell him this, but I thought he should have hewed closer to the truth. It always strikes me how much of storytelling involves a delicate balance between truth and drama.

Later, alone in my room, I searched online to see if Carl had any published work. I found none. Instead, I read an article about a securities broker-dealer named Allen Carl from Panama City who had lost his license due to unethical financial dealings and had been discharged from the bank where he worked.

I wondered if that’s why, at eighty-two-years old, Carl still worked. I wondered if that’s why he wrote.

As the conference got underway, Carl and I found ourselves on separate paths. Carl was a paying attendee with the freedom to engage with all the conference’s offerings, including agent meetings and beach yoga. As a recipient of a scholarship, I had duties; the organizers expected scholars to act as ambassadors, setting up the assembly hall each morning and stocking coolers at night. My moments away from my responsibilities were spent at the beach, where the ocean glimmered with a bright, Caribbean blue that occasionally turned a brilliant shade of green. The sand, too, was an unusual white, cool underfoot and smooth.

I noticed that Carl avoided the beach. He spent his free time with the “senior group” – the other older attendees. At the assembly hall during craft talks, he always sat in the same seat by the south-facing window, notebook in hand but never writing anything down.

The other day, on New Year’s Eve, I found myself sifting through my closet full of old writing notebooks, half-typed stories, and daily observations—the last corporeal remnants of my work. Although the ink had faded on many pages, snippets of text caught my eye, evoking memories I would have otherwise forgotten, such as the sight of herons clutching fish in their beaks—an image that transports me back to that Florida beach, the sand soft and powdery, like almond flour beneath my toes. Inside one notebook, I found my conference nametag, the ink still legible under the plastic, despite the decades that had passed.

I never saw my name on the cover of a book. That dream slowly faded until one day I realized I hadn’t thought about it in years. In other respects, I count myself immensely fortunate. I am grateful for reaching this age, for my wife, who still kisses me every night on the neck, despite my wrinkles and infirmities, for the son I raised, who enjoys spending time with me to this day, and for the advancements in healthcare that have mitigated the harsher symptoms of my own disease; these days, memory is slippery. Sometimes I forget the names and faces of those dearest to me, including, sadly, my own wife’s.

Technology, too, has become a great tool. I was initially reluctant to embrace the idea of an AI-powered device implanted directly in your brain. I was afraid of relinquishing control, of losing the human touch. But, as the technology took hold and the practice of writing evolved, and as finding the right words grew increasingly challenging, I decided to give it a try. Now, I am able to see my words on the page once more. I am able to hear my own voice in the text.

As the conference progressed, my interactions with Allen Carl outside our cottage became rare. Our workshops were held in different buildings, and as happens at such events, social circles had formed. I gravitated towards a small group of poets, among them the mysterious poet from the first day. Poets always seemed otherworldly to me, perceiving the world through a lens unlike that of more logic-driven writers like myself. Instead of seeking answers, they posed questions, viewing life as a collage of images that did not necessarily need to be explained but could stand side by side to reveal deeper meaning.

I spent my days with these poets by the beach, soaking in the sun and paddle boarding when the waves were gentle. In the evenings, we would gather by the shore, smoking cigarettes and passing around guitars and singing Dylan and Johnny Rivers, with the moon shining overhead like a slice of frosted cake, the stars scattered across the sky narrating ancient tales of gods and men. The mysterious poet would recite verses she had written during the day, on themes of existence and the transient nature of beauty. At these moments, I felt part of something timeless and profound. I had finally found where I belonged. My only wish was for time to stop.

I wrote little that week, slept less. Carl’s alarm clock would jolt me awake each morning just as I would doze off.

“Good morning,” Carl greeted me. He was shirtless at the kitchen table as the sun began its slow ascent. I grabbed a couple of K-cups from the nearly empty box. I felt guilty for consuming most of Carl’s coffee supply, so I lingered in the kitchen, prompting him to share his publishing experiences.

“You published a book?” I asked, surprised, as my prior searches for any publications under his name had come up empty.

“I used a nom de plume,” Carl said. “Can’t let my clients think I’m neglecting them for writing, though that is often the case. Every day, when the stock market closes at 3PM, I close my office door, log off my email, and get to work.”

The Keurig labored over our second cup. “A book?” I said again.

“Yep. Last year.”

The coffee burned my tongue, I choked on my words. “That’s fantastic,” I said. “Where can I get a copy?”

Carl chuckled. “Trust me, you don’t want it. It’s terrible.”

“Oh.”

“I paid for a publishing service. Total scam. They only edited the first seventeen pages and claimed that’s what the contract specified. The rest of the book is a mess.”

“At least you have a book,” I said.

“Next one will be better,” Carl said. “It’s about a writer who writes a book about sex and porn in the publishing world. I’m calling it This is a Dirty Book. It’ll sell like hotcakes, and it’s going to be a big screw you to the major publishers. I’ve already lined up a different company that promises to edit the whole manuscript, design the cover, and handle marketing—all for just ten grand.”

At the time, I wasn’t familiar with the predatory nature of some vanity presses—companies that offered book publication but with the writer bearing all risk, exploiting the dreams of inexperienced writers—but later, in workshop, we critiqued a crime novel by Dora, a local author with moon-white hair, a walking cane, and a thick Floridian accent. She had been an elementary school teacher before retiring and trying her hand at crime drama. Her novel was about a Russian spy that blended famous historical events and make-believe scenarios.

Despite our extensive feedback in workshop, Dora seemed unfazed as she handed out signed copies of the already published book.

“We’re sorry,” we murmured, handing back our annotated versions.

“No, this is wonderful,” she said. “I hadn’t considered these points. They’ll be great for the second edition.”

Like many, I once viewed vanity presses with skepticism. But now, as my time on this Earth ends, I wonder: how many dreams and stories did these presses preserve? How many lives were touched by these stories that might have otherwise remained untold?

I never discovered Carl’s pseudonym. Never found any proof of his work, either. Searching for This is a Dirty Book led only to dubious websites. I used to believe that interest in sex dwindled with age, but that proved wrong. Young people, like I once was, find geriatric sex repugnant, but as you grow older, you come to learn that desire doesn’t fade with age.

Carl understood this well. Writing about sex at his age contained more truth and honesty than what many writers chose to write about, and that week, in that trailer by the sea, I bore witness to such truth.

It was toward the conference’s close. I was running on little sleep, having spent the night in another deep discussion with the mysterious poet. After workshop that day, I rushed back to the trailer. Carl wasn’t there, so I took the opportunity to catch up on sleep. I retreated to my bedroom, where I closed the door, turned off the lights, shut the blinds, and settled into darkness with a towel draped over my eyes.

Soon, however, the front door to the trailer opened. A woman’s voice cut through the quiet. “This is where the magic happens?” she asked. She had a Floridian accent, an unmistakable drawl.

“If you mean my writing, then correct,” Carl said.

“Do you cook?” she asked as they shuffled through the kitchen.

“Not really. My wife handled that.”

The sound of footsteps grew closer to my room. I was pinned to the bed, frozen. Carl introduced my room, “This is Dan’s room. He’s from New Jersey and writes what you’d call literary realism.”

“Would I have heard of him?” she asked.

“He’s not famous,” Carl said, dismissively. “Nice guy, but he’s one of those writers who doesn’t want to be read. He’s a nobody.”

Sitting alone in the dark room, my blood ran hot with indignation. But then the cold truth dowsed the fire. That was the first time that I considered myself a nobody. It would not be the last.

Carl and Dora continued down the hallway to his room. I heard the door shut. I sat still for several minutes, the sounds of muffled conversation giving way to more intimate noises. I heard the creak of Carl’s bed, the rustle of the sheets, Dora’s moans; the proximity of our rooms left little to the imagination.

After half an hour, they emerged from the bedroom. In the kitchen, Carl offered Dora one of my Hawaiian chocolates. I remained in my room, wounded yet wondering about the connection between the act of sex and the act of writing. In each case, there is a desire to be understood. Our desires and our writing are so often entangled, and even as we age and our bodies betray us, as we become reliant on medicine and technology, the need for connection still remains.

As I reflect on that moment, one detail lingers in my mind—a detail I noticed then but did not consider further until after Allen Carl became a memory, buried as it was by his other, more hurtful words.

My wife handled that.

During our conversations, Carl frequently spoke of his son, a former football player at Ole Miss who now worked in finance in Tokyo. He rarely mentioned his wife. I assumed he might be a widower. It wasn’t until I found Carl’s obituary two years later that I discovered that his wife had passed away one year before him, meaning she would have been very much alive that summer.

The possibilities were endless. Maybe they had an open marriage. Or, perhaps the reality was simple: Carl had been unfaithful. I wanted to know why. Was it out of boredom? The weariness of his wife’s aging body? The cruel ticking clock? Or was it simply because he wasn’t a good person?

The true reasons behind Carl’s actions remained a mystery. But now, as my time on this Earth ends, seeing how my own wife looks at me—with absolute love and clear acknowledgment of my harsh decline—I have a better guess, and I can understand Carl’s choices; the selfless side of me would want the same opportunity for her.

On the final day of the conference, I woke to the familiar chime of the stock market bell and found Carl pacing in the kitchen, muttering to himself.

I had been avoiding him since the Dora incident. Though I did not know it at the time, I can see now that his words had a profound effect on me. They marked the beginning of my own slow abandonment of the literary world.

“Can I ask you to do something?” Carl said.

“Of course,” I said. I have always found it impossible to be rude to strangers.

“Can you take a video of my reading?”

That night, there was an open mic reading for all paying attendees. As a scholar, I had already gone, reading a scene about a sushi chef and his culinary antics that was warmly received.

“Of course,” I said—though I imagined how I might ruin the recording by filming vertically.

“I’m still not sure what to read,” Carl said. “I could read from This is a Dirty Book, but we only have four minutes, and I don’t want to come off as some old pervert.”

I suggested flash fiction.

He shook his head, “I’ve only written a few short things. Never bothered to workshop them. I suppose my novels are for the world, but my stories are for me.”

In the kitchen of our trailer, Carl’s gaze drifted to the window, where the sun climbed higher in the early morning sky, marking time in the most ancient way. “My hope is that I can be honest in my stories in ways I have not been in my life,” he said.

As he spoke, my hand traced the chipped edges of the kitchen table. His words erased my anger toward him. That had been my hope, too. Every project held the promise of a new beginning, another search for veiled truth, not in life but in the pages of our stories.

The last day unfolded leisurely; there were no workshops. I joined the poets at the beach. It was a rare emerald day where the algae tinted the water a mesmerizing green. Later, we attended a book signing and shrimp boil in the courtyard beneath the clock whose hands were frozen on midnight.

Carl had been absent throughout the day but arrived for the evening’s readings. I sat to the right of the mysterious poet. Her sandal tapped in time to each poem’s meter, a habit, strangely enough, she shared with my wife.

It was soon Carl’s turn to take the stage. I started recording on my phone. He approached the podium, head bowed, focused intently on his papers. He told us that he had written the piece while at the conference.

“The atmosphere felt charged,” he began to read, “as if a veil of smoke cloaked the room, each table with its own secrets. Some whispered truths, others lies. I sought solace in my corner, my past aching like old wounds. As I rolled a cigarette, the whisky soothed me, and couples swayed to slow dances. It wasn’t until Johnny Rivers’ guitar filled the air that I truly listened, evoking memories of a different time.

“I reached for her hand and we danced alone, like a moment long passed. The dance was smooth, ethereal, as if we were the only two in the room. Her head rested against my chest, a soft touch that felt like home. We moved with ease, our intimacy enveloping us like a gentle rain. In a whisper, she pleaded, ‘Please, never forget me,’ and she kissed me on my neck, a sensation that would linger like a warm scar.

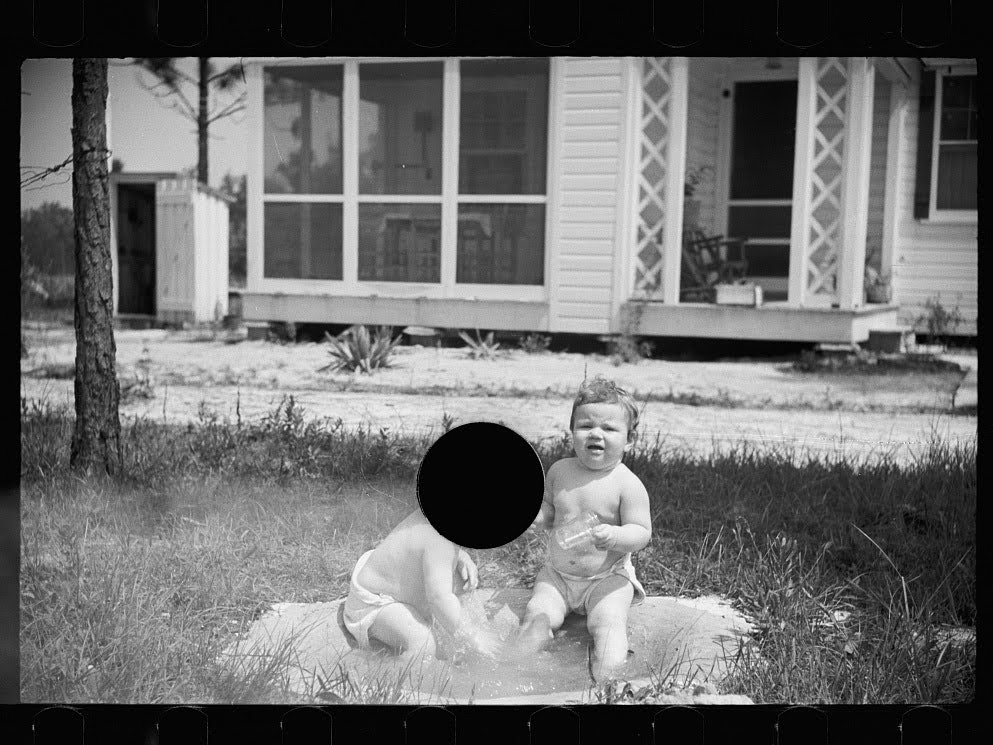

“That night was a montage of our life together: our first words carried aloft by the wind on a white beach, the ocean a backdrop of blue and the occasional otherworldly green; our laughter mixed with our son’s confused chuckles when he once interrupted us in the act, his innocence framing our love. On the dance floor, I dipped her like at our wedding, her smile cracking open my heart.

“But then the song ended and the music stopped, and I was alone again, my only companion the same old cigarette. I ordered another drink, the cold slowly giving way to a reluctant warmth.”

That night, Carl’s story haunted me, but not as it one day would. In the foolishness of youth, I deleted the video, a decision I now deeply regret. I did not realize it at the time, but I had captured something profound, something that should never have been erased. Proof that he had found his voice. Proof that even nobodies like us could find our voice before our time on this Earth ends.