Bill Gusky

Great Blue Heron

To avoid waking his brothers, he dressed in the bathroom: Goofy Grape t-shirt, cargo shorts, green sneaks.

He tip-toed out through the kitchen, then down the stairs to the basement, and the small glass terrarium. Lifted its plywood lid, scooped up a cool tangle of gray and orange, tucked it gently into a cargo pocket.

He climbed the stairs and ever-so-gently opened and closed the back door with its noisy jalousie window. Unlocked his ten-speed from the back porch post. Pedaled down the short driveway, into the maze of white streets lined with one-story houses built exactly ten feet apart.

Street signs passed, green strips atop tall poles with names in white letters: Bluebird, Goldfinch, Cardinal, Robin. All the streets in his maze had been named after birds. He broke out at the corner where Swallow swept into Humes Lane.

On Humes he passed his school, the fire station, the junior high school, and the athletic fields beyond. The mazes fell back a half-mile on either side here, and the sudden openness exhilarated him, electrified his legs, made him stand on the pedals. He took great hungry bites out of the long ascent to the top of the river bluff, pumping with all his weight until sweat blinded him and his muscles burned. He walked his bike up the last hundred feet.

The early morning air held a metal tang, a hint of the afternoon broil to come when a blazing sun and lambasting humidity would subdue every living thing not blessed with air conditioning.

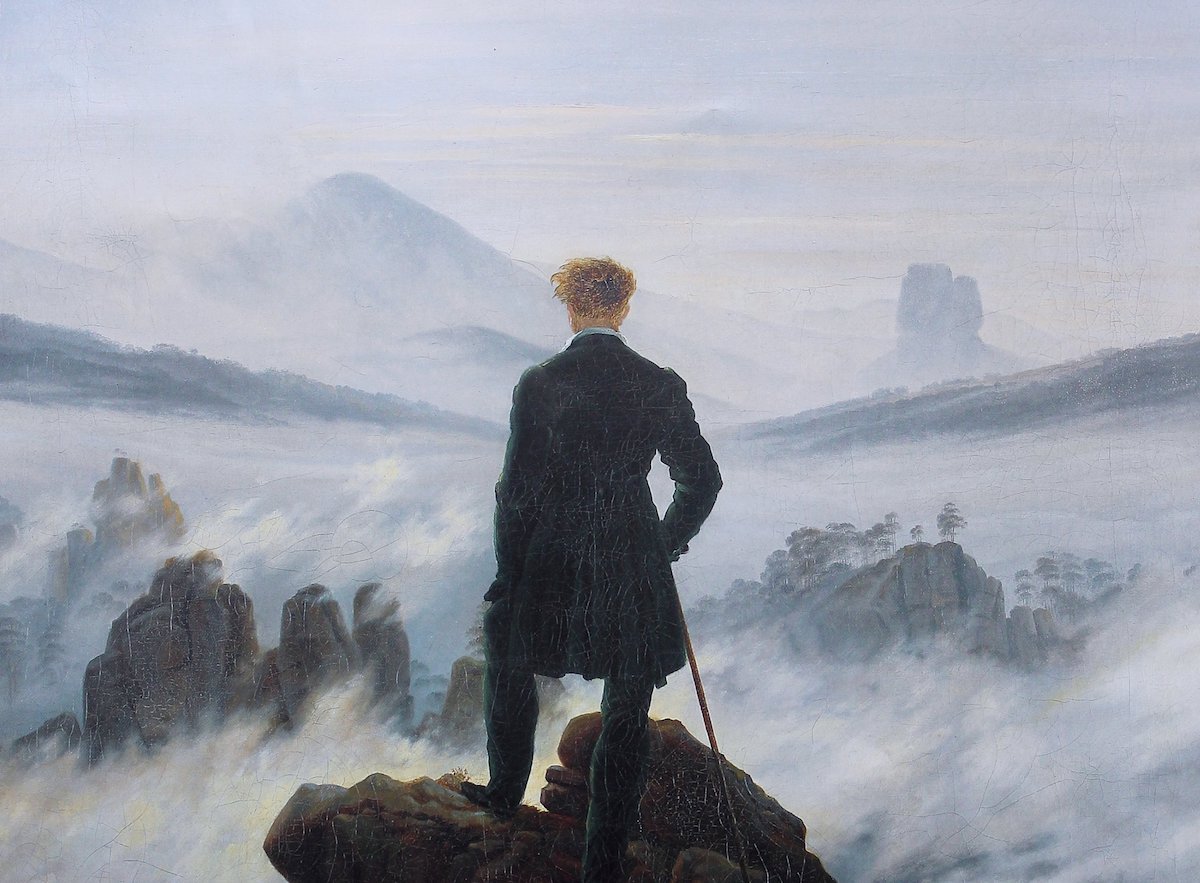

At the hill’s crest he took a breather, and cast an eye backward toward his world from on high. A sun-blasted desert of rooftops the color of bleached bone stretched out to the eastern horizon. Nearly everyone he’d ever known lived beneath those rooftops. His parents, of course, and his brothers and sisters. Three kids he considered friends. And all the other kids, hundreds, it seemed, who either confused, intimidated, or simply scared the crap out of him. Ghost kids who slunk along the walls at school and never spoke. Kids who dressed strangely and only discussed Jesus. Kids who, like him, were about to enter junior high, who talked about getting drunk or stoned as though they’d been doing it for years. Explosive kids. Angry kids who only smiled when they were dealing out pain.

And adults, holy crap, the adults. Neighbors, friends of his parents, parents of his friends. The ones who pretended to like him. The ones who hated him for reasons he couldn’t comprehend. Teachers who opened up warmly to him like flowers, and teachers who were cold, indifferent, almost not there at all. Men and women who doused themselves in cologne, for some reason. The angry ones, the nervous ones, the constant smokers. Adults who were clearly falling apart, singing to themselves while trimming their shrubs late at night, or crying openly as they walked around the block. Adults who never had a nice thing to say about anyone. Adults who seemed to float above the others, always cheery; as a younger child he’d liked these the most, but recently he’d begun to sense deep sadness within them, and he found this confusing.

Midway through his eleventh year, his existence felt like a mountain trail whose every up-and-down grade, every kink, every turn, came from avoiding people and situations he found bewildering, stressful, or demeaning.

From this high bluff he could turn his back on that inscrutable tangle and set his gaze westward, out across the river, where serene patchworks of olive, brass, and emerald fields extended forever. He quickly lost himself in the tiny details. Farmhouses, which he imagined were open and airy, and smelled like apples. Barns and silos freshly painted. Roads that weren’t maze-like at all, but long and unbending. Tiny sparks drifting slowly across the fields that sometimes swelled to bright stars: the rising sun reflecting from tractors and other equipment as farmers began another long working day.

He tried picturing their view looking back toward where he stood. The high bluff fluffy with oaks, maples, sycamores, dark against the bright morning sky, and the gargantuan electric towers like robot invaders, a train of them tumbling down toward the river and across the fields, stringing their mysterious humming wires along. He wondered if the farmers could see him standing there, and if they knew about the mazes of homes hidden far behind him. Could they even imagine people living like that?

Legs rested, he pedaled to the far side of the bluff where the road dropped steeply away, disappearing in shadows and foliage.

He could walk his bike to the bottom, as he’d never done. It would take longer than riding, but it was safer. It was the kind of safe decision his father or mother would make, because a nasty hairpin turn lurked somewhere in the gloomy greenness far below. He could never quite keep pinpointed in his mind precisely where it lay, and it threatened to end him each time he defied it.

His breath became heavy as he gazed into that dark tunnel of trees, trying to decide if he was really going to challenge that hairpin turn again. His guts tightened, and the gloss of sweat on his brow began to drip.

He eased the front wheel of his bike to the edge of the drop.

Took a deep breath.

And went over.

The acceleration was instantaneous. Frightening.

A chill raced across his skin, the wind instantly drying all sweat from his face, his hair, as a terror bright and pure and wild banged within him like a panicked bird trapped in a coffee can. He clenched his jaw so hard he tasted blood. He squeezed the ten-speed’s brakes until his hands screamed and the pads smoked.

The hairpin turn! It ambushed him, rushing his front tire so rapidly he panicked, yanking the handlebars left and bracing for the wipe-out that had to follow. His Saturday was about to end in a long, bloody skid mark as the ten-speed whipped round, yet somehow, in spite of his sweltering full-body dread, he persuaded the bike to screech to a hard stop.

Long moments later, his breathing resumed.

He swung a leg off, put the kickstand down. Walked trembling circles yelling son of a bitch over and over, hearing his voice ring back through the woods. Shaking the blood back into his hands. Feeling the trickle of sweat down his back.

Looking back up that steep road, he wondered how he’d ever saved himself. He vowed, as he’d done every time before, that he’d never ride down again.

When he’d finally calmed himself he set out, walking his bike along a path that descended through milkweed, sumac, and thorns.

He passed the graves of houses long gone, their vine-covered foundations brown and crumbling.

He passed fire pits filled with charred wood and soot-covered beer cans.

As the river came into view a peeling, faded sign as large as his bike wailed like a vine-shrouded wraith DANGEROUS UNDERTOW – DO NOT SWIM. It seemed every year someone ignored the sign, only to disappear beneath the choppy chocolate-colored waters. He’d never known any victims personally, but their names came up at school, and in the local paper.

He wasn’t sure what an undertow was. He imagined kids swimming in the muddy water, and a giant hand, crinkled and twisted like driftwood, rising up through the murky water beneath them, grabbing their legs, and dragging them under. Towing them along the bottom as they screamed bubbles. The image was terrifying enough to keep him from ever considering a swim here.

On this side the river was bounded by a dense strip of woods, and a narrow trail. He followed the trail until he reached a thicket he’d come to consider his own, because it was big enough to hide his bike, and it included a sapling he could chain it to.

Cicadas buzzed high and loud all around him as he clicked the padlock shut. Their quavering chorus mingled with the calls of mockingbirds, blue jays, grackles, and red-winged blackbirds, in a fog of sound so dense he felt it in his head, in his chest, at the core of his being. It made him feel woven into the fabric of the air, and of the woods.

He became conscious of something heavy within him, just then. A weight that hung in his chest, and extended rubbery tentacles into his head, and through his belly. It was there all the time, he knew. But something about the cicadas, and the noisy birds, and being alone out here by the river, caused the weight to loosen its grip on him, and to slip away.

The sudden lightness made him want to yell, and he filled his lungs, raised his head. But a yell wouldn’t come. Yelling here seemed wrong, somehow, like spraying graffiti in an art museum. The thought of it was strangely, surprisingly hilarious, and a great, open laugh exploded out of him. The laugh startled him for its fullness, its generosity, the way it poured freely from his throat and rang through the woods. It was the laugh of an older person, he realized. The laugh of a man.

Once it faded, he tried to laugh again and make it sound exactly the same. But it felt forced this time, and didn’t sound as nearly as good. In fact it sounded so bad he felt a flush of embarrassment, and he yelled Hee ha hee hee ha ha hee hee har har har! on the chance anyone might be listening in, to show that he’d been faking it all along.

He picked his way through the dense woods using a stick to push the thorny undergrowth aside, until the foliage above gave way to a sky the milky color of an eyeball. He knew the black mud beyond the woods was slippery and at times quite deep, so he stepped carefully across its ridges and grooves until the river flowed only a few inches beyond his sneakers.

Mentally he knew that this, like all rivers, was simply water flowing from one place to another. Yet it was unlike any other water he’d ever known. The brown river oozed thickly, almost like milk. It eddied, it swirled, it twitched. The river had a life all its own, like a giant, serpent-shaped animal laying across the land, a mammal whose pelt erupted everywhere in mouths, and hands, and eyes.

The river laid claim to everything around it as part of itself. In spring it devoured houses and cars. He’d seen it himself, seen the rooftops awash, the lines of telephone poles descending into the flooded plain.

He stood still at its edge, sinking slowly in the black mud as the strangely living waters slid silently beside him.

And he waited.

Because the river, he knew, held something for him. Something it gave up whenever he stood long enough and quietly enough on its bank. He’d discovered it not long ago, and he’d learned to wait for it the way he’d learned to wait for every good thing. He controlled his breathing, closed his eyes half-way, and imagined the world before him as though it were a painting of itself.

It wasn’t long before a feeling geysered from deep within, and rose to fill him, the way floodwaters fill a basement. The feeling was of the river running, not beside him, but through him.

Like the steady stream of his own breathing.

Like his blood.

His heartbeat.

It froze him there in space, staring into the oozing waters, lost in their timelessness.

The river was so much older than the mazes of homes, so much older than his house and the little trees planted around it. It was older by far than the oldest people in his world, his grandparents and great-grandparents.

Time, in fact, meant nothing to the river. It barely noticed the barges and Jon boats sliding along its surface. The bridges and even the dams cutting across it were matters of idle curiosity. Only the land itself was of interest to the river, because only the land was older. The river gave itself wholly to its wrinkles and valleys. It trusted the land to give it shape and direction.

A pair of blue jays screeched nearby, battling over a dead minnow. The sound startled him, and he remembered why he’d come.

He reached into the pocket of his cargo shorts and removed its tangled passenger. Straightened it between his hands into a shiny, crinkled line barely a foot long, gray on top, bright orange below, with a neck ring that matched the gold of its eyes.

He admired the snake’s perfection, which remained even in death. And he felt sorry for it.

His uncle found the snake in the wild two years prior, and had given it to him. Snakes became an interest they shared. He fed it worms from the grass, and from a bait shop at a big old house surrounded by weeping willows and bird baths. He enjoyed watching the snake approach a live worm dropped onto its terrarium sand. Watching it seize the worm and swallow it end-first, the lump oozing along its shiny body. At times he’d felt badly for the worms, but then what else could he feed a snake? Lettuce?

Now, holding the dead snake over the swirling river, he closed his eyes for a moment, not so much in prayer, or to say goodbye, but to make sure he felt right about what he’d planned to do.

And he did. In fact, he felt good about it.

He drew his arm back and threw the snake across the water. It was a bad throw. The snake pinwheeled, and its tail caught the surface only eight feet away, with the rest falling after.

The snake seemed to revive for a few moments as gentle waves made it slither, head to tail. He kept it in his sights as the river carried it downstream, until it was too far away to see.

That’s when he realized he’d sunk into the mud up to his ankles.

When he pulled his right foot free, its sneaker remained deeply mired. He tried crouching on his left leg to pull the sneaker out, but stumbled, sank his bare right foot in deep, and had to tug it free again. After a few more tries he managed to wrestle the sneaker out and stomp his muddy foot back into it. When he pulled the left out he was grateful that, this time, both sneaker and foot came free together.

As he picked his way back across the mud to firmer ground a shadow passed over him, over the muddy bank, and over the water.

He turned to see a great blue heron, stroking the air with its massive gray wings as it settled into the water up to its orange knees some distance downstream.

Easily as tall as he and maybe taller, the heron had fixed its gaze on something in the water, something moving slowly in its direction.

He saw the splash before he heard it, and by the time he heard it the heron had already retracted its dripping head. A curlicue of gray and orange dangled from its dagger beak. The heron snapped forward, swinging the snake’s body entirely into itself in a single darting motion. A small lump traveled down the silvery hook of its throat, until it disappeared just above its graceful breast feathers.

The heron’s eye, he realized, was every bit as round and gold as the snake’s. It glared at him now as though waiting for a signal, some acknowledgment that something important had taken place.

It was as though the heron wanted to be sure he understood.

He realized in an instant that he did, in fact, understand. The understanding defied words, it was a steep, full-body rush of comprehension he could only feel, he could only thrill to. It ignited a strange brightness in his chest, a glow that spread, and made him giddy. It came to him as an assurance that the river had accepted him as its own. That in its embrace life would be okay, and things much stronger, and older, and larger than he were in charge. That he could always return to the river, even in his worst times.

His face opened in a grin so massive it was almost painful.

The great blue heron lifted its head, as though satisfied. It turned away, opened its gray wings, sprang from the water, and shoveled air beneath itself, climbing higher and further away. He watched it become a child’s drawing of a bird before vanishing, finally, into the steamy brightness.