https://cutleafjournal.com/content/the-boy-in-the-high-school-science-room-and-other-poems

The Boy in the High School Science Room

He’s been looking for something simple

like hydrochloric acid or magnesium

for the past half hour, but he’s been caught up

by other things: the mummified cat on the top shelf,

the model of a human brain

still tucked away in the model of a human head,

Copernicus, Galileo, Einstein,

bauxite, obsidian, and gypsum.

Passing by the window, there are more

distractions, the varsity football players scuffing each other

in practice, all the weepy-eyed girls

staring astonished as though

these young men could defy physics, like wishes,

to give them anything they want. This will never happen,

but they don’t need to know that. A few steps farther,

the clear upside-down

bell of the vacuum chamber waits

for its once a year feeding of balloons and marshmallows,

ready to feast on the air,

drawing it out in one mortifying extended breath.

There is one teacher for all these sections,

a balding minister of a Baptist church,

who tells the boy, quoting a thousand sermons,

he is going to Hell

unless he accepts God into his life.

For a few moments there is a presence

in everything, something blue in the flame

of Bunsen burners, something waiting

in the mongrel pup stored in a jar of formaldehyde,

something in the atoms of helium

that pushes it to float upward toward its own

dispersion. Nothing that holy could exist

on earth. So he resigns himself

to tarsus and metatarsus, tibia and fibula.

The quivering skeleton in the back room

all the kids guess is real,

wondering who it was, and if it suffered,

and, if there are souls in heaven, is it there?

But that is another problem, a test

with no observable evidence other than these bones

hanging from a metal pole in the darkness of a storage closet,

ready for its numbered parts to be labeled

and displayed and reassembled.

He could search all afternoon, tomorrow,

and the day after that for whatever it is

he has been sent to find. Outside this room,

he knows the stars are moving farther away.

The light they send is so fleeting and old.

Journal Entry: Mapping Stars in City Light

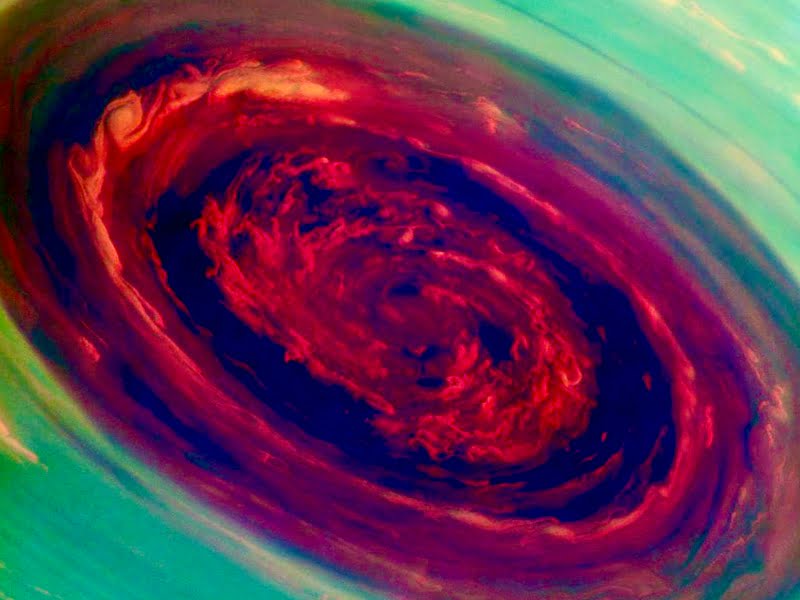

Sirius, the dog star, and Procyon, the little dog,

I’m in the spill of streetlight

trying to find the brightest stars. Really,

I should know better, here

in the midst of town where the aura of buildings

and roadways is stronger

than constellations. Growing up in the country,

I could see every pinpoint

in the sky, the dancing arm of the galaxy aglow

across the night. Arcturus,

bear watcher, in the last stages of its life, and

Vega, the vulture, there are

so many animals in the sky, so many dead heroes

to keep them company.

I’ve often dreamed myself among them, a few

barely blinking lights

in a cluster somewhere near Orion’s heel.

Which is called Rigel,

the place where Scorpio stung him in fiercest

battle. But I’ve done

my research—Orion was a giant and the worst

sort of man, the kind

we should all reach up and tear from the sky,

all those stars falling

in fire upon the world. Canopus is a supergiant,

and Capella is actually

four stars. I have a hard time orienting myself at this

confluence of rivers bordering

town, the way they snake and change direction.

Betelgeuse is a lion

waiting on the other shore, and Achernar is the end

of this river, which is an ocean,

which is another place too wide to see all at once,

at least from here. Eventually,

I will go back inside to lamplight, watch a movie

I’ve seen a dozen times

before, maybe something science fiction.

Something that allows me

to weave in and out of stars, and all the fabled

creatures that live among them.

Not A Sonnet

—no thanks to Shakespeare

My lover’s eyes are nothing like what you’re thinking,

and when I use the word my, I don’t mean to denote

ownership or dominion. I intend a certain intimacy—

sitting at dinner, our knees touching—or later, asleep,

our arms, our hips, our hands fallen where they may.

May what, I couldn’t say. And when I say lover,

I don’t mean to imply a strictly physical relationship,

a constant passion ravaging the body. We walk

along grocery aisles comparing prices. We sing

and talk and answer tv gameshow questions. Yes,

I said ravaging. Sometimes passion shakes your bones

brittle, deprives the body of oxygen, snaps the junctions

in the brain. My lover’s temperament is earthquake

and typhoon, tornado and lightning. I wouldn’t have it

any other way. And when I drown in the deepest

oceanic trench or suffocate in the exosphere, my lover

is my metamorphosis pulling me back to land, restarting

my heart, blessing air back into my eager, ravaged lungs.