Louise Marburg

Too Late To Play

The Powerball jackpot is over a billion dollars. It’s all anyone can talk about. At my office, people are contributing to departmental kitties; they’ll buy as many tickets as they can with the money and share the jackpot if they win. The departments are not unlike the cliques I remember at J. Fenimore Cooper High, where I endured four years of inane pranks and being called Loo-eez instead of Lewis. The Legal Department is the equivalent of the coolest group because they all have law degrees, though you’d have to be a fuck-up of an attorney, in my opinion, to work for Social Security. Human Resources is full of haughty women who wear power suits and clacking heels, and Acquisitions and Grants has the caché of being mysterious because no one knows what they do. Information Technology, where I work, is superior only to Administrative Support. There are nineteen of us in the department, and ten bucks is the ante. When someone asks me why I’m not playing, I point out the one in 340 million probability of winning, which makes me “no fun” and “a bummer.” I’m a recovering gambling addict. I haven’t made a bet in three years.

A guy I work with comes into my cubicle and perches half-assed on my desk. His name is Gary and I guess he’s the closest friend I have here, though we’ve never done anything more intimate than grab a sandwich at lunch.

“Marie says she wants to retire to Sarasota,” he says. “But I’m partial to the Bahamas.”

It takes me a moment to remember Marie is his wife. He’s talking about what he’d do if he won the Powerball jackpot.

“I spent my twenty-third birthday in Nassau,” I say. I never laid eyes on the beach, but even now I could describe the décor of the hotel casino in detail.

“I’m talking about the out islands,” he says. “Andros, Cat. I hear the fishing out there is amazing.”

“It’s not even debatable that you won’t win,” I say. I am indeed a bummer, unquestionably no fun. I would start gambling again out of resentment and envy if I knew anybody who won.

“A guy can hope,” he says.

I perfectly understand hoping for something that very likely won’t happen, I spent years doing just that, but I shake my head as if exasperated by Gary’s foolish ways. “Hope is an invitation to disappointment,” I say.

“What’s with you these days, Lewis?” He’s got a zit on his chin that’s about ready to blow. “What’s got you so down in the mouth? Girl trouble?”

The last trouble I had with a girl was with a prostitute I picked up near the railroad station over two years ago. She took my bottle of Jack and my wallet. “That’s it,” I say. “How did you know?”

Gary nods sagely. “I had a feeling. What’s her name?”

“Clementine,” I say. “She’s a concert bassoonist and teaches clog dancing on the side. Multi-talented.”

“Sounds like it,” he says. I can see by the empty expression on his face that he’s never heard of clog dancing and doesn’t care enough to ask what it is. On weekends he makes lawn whirligigs out of scrap metal and sells them on Etsy; his favorite movie is Avatar. He claps me on the back, says something about a deadline, and retreats down the hall to his cube.

At five o’clock I log out and go get a doughnut at a place called Sweet Lily’s. I’ve been coming to Lily’s and buying a doughnut after work ever since I gave up gambling. My Gamblers Anonymous sponsor at the time suggested I do something in my free time to occupy my mind. He was probably thinking of a pottery class. I don’t know what he was thinking. I had lost my car and my apartment and even some of my clothes and was living on my mother’s couch in her tiny condo near the beach. I went to GA at her insistence, but I fully intended to gamble again once I got back on my feet. Then one day I stopped at Lily’s and bought an old-fashioned cruller. It was about eight inches long, crusty and golden. The dough inside was cakey, not too sweet; the crust was crunchy, oily, warm, a miracle of taste. I didn’t think about gambling at all while I ate it, which must have taken five minutes. Five minutes was a personal best when my desire to gamble was so overwhelming and constant.

There’s a bunch of school kids waiting for doughnuts, but the line moves pretty fast. Lily’s behind the counter. She’s as skinny as a greyhound, eighty-six-years-old, and has a smoker’s hacking, phlegmy cough that’s both worrisome and gross. It’s Monday so I order a chocolate crème puff. Lily scoops one off the latticed wire shelf and slides it into a brown paper bag. She asks me if I’m still working at Social Security, as if she hopes I’ll say I’m not. I would work somewhere else in a heartbeat if I could find a better job; I’d trade my studio for a one bedroom, too, if I wasn’t still paying off a mountain of debt from cash advances on credit cards.

The usual crowd is loitering on the sidewalk outside the shop. I say hi to Penny, who’s just gotten divorced, and to her foxy best friend Olivia, and to a pair of retired twin brothers named Gil and Howard Platt. Julia Bowman looks bad on the best of days—a missing incisor, pocked complexion, stringy dun-colored hair—but today she looks extra pale and addled, and I wonder if she’s back on meth. I join Kevin Moffet, a guy about my age, not young but still far from old. He’s wearing a three-piece pinstripe business suit even though he’s unemployed.

“Job interview?” I say.

“I aced it,” he says through a mouthful of glazed doughnut. He aces every interview he goes on but never gets the job.

“You think Julia is using again?”

He considers Julia, who is picking at her jelly doughnut. She’s standing half on and half off the curb, the parking lot beyond her. “Hey Julia,” he says. “How’re you doing?”

“Fine,” she says and looks away. Usually, you can’t get her to stop talking, she barely takes a breath. There’s nothing anyone can do about her, I know that, but I go over anyway and try to get her to smile.

“Can I borrow some money?” she says.

“I don’t have any.”

“I only want ten bucks for a few Powerball tickets.”

I take a bite of my crème puff. Nobody here knows about my addiction. Outside of my GA meetings, few people do. I don’t try to hide it except from my colleagues at work, but it’s awkward to introduce a fact like that into normal conversation, then you don’t and at some point it’s too late. “I’m definitely not loaning you money for that; you might as well throw it away.”

“I got my tickets,” foxy Olivia says. “Me and Penny went in on twenty. We’re watching the drawing at my house tonight.”

“I bought thirty,” Kevin says.

“What would you do with a billion dollars?” Penny says, stabbing a yellow pencil in and out of her riotous salt and pepper curls. “I know what I’d do. I’d quit my job, number one. Then I’d buy one of those mansions at the beach.”

“That wouldn’t make a dent in a billion dollars,” Kyle says. “I want to buy a tech company like Microsoft or Google, one of those. I’d make myself CEO.”

“Are you all talking about the lottery?” Gil slips his fingers beneath the collar of his flannel shirt and gives himself a good scratch. “A billion-dollar jackpot! Imagine that.”

“What about you, Lewis?” Olivia says. “What would you do with a billion dollars?”

I asked her out once and she turned me down, but that was long enough ago that whatever awkwardness there was between us has faded to an occasional twinge. “I’d give it all away to worthy causes,” I say. Everyone groans in disgust. I finish my doughnut and throw the bag into a brimming garbage can. “I’m not going to play. The chance of winning is infinitesimal.”

“But there’s still a chance. Penny pokes at her hair and frowns at me. “Don’t you believe in chance, Lewis? No matter how high the odds?”

She’s not half bad, and now she’s divorced. Older than me but so what. “I’ll take a chance right now and ask you out,” I say.

“I’m not dating yet,” she says. “I only signed the papers last month.”

She wouldn’t have said yes even if she was dating, which she might be, she could be lying. Women aren’t attracted to penniless men, and who can blame them for that. If I had a billion dollars, I’d have a different date every night. Like doughnuts but so much better.

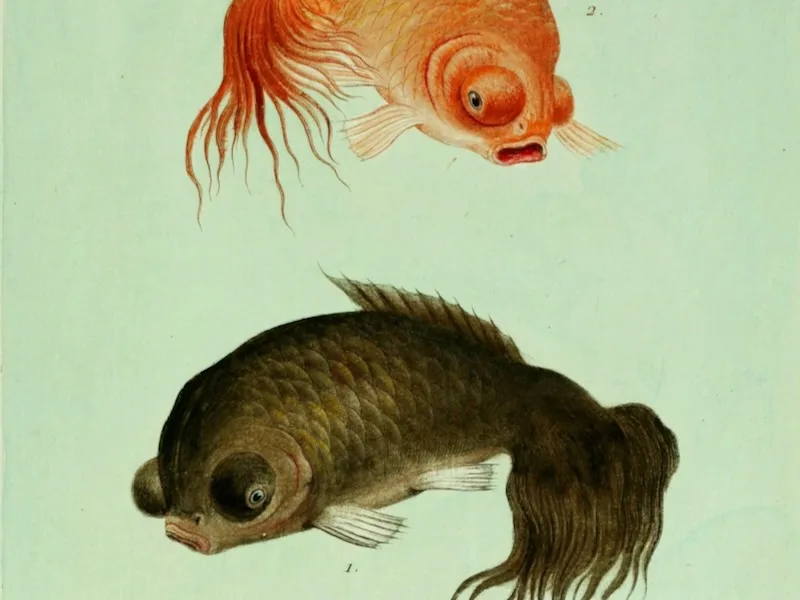

I have time to kill before my GA meeting, so I drive to the beach and sit on a dune for twenty minutes watching the setting sun do its technicolor thing. I take off my shoes and socks and bury my toes into the cold sand until my feet are covered to my ankles. When I was a kid, I used to fish off this beach with my friends, surf casting for blues and bass. I remember the sudden hard tug when I snagged a fish on my line and the thrilling fight to bring it in. Half the time I lost the fish but if I caught it, I threw it back. I had a lot of friends when I was little, but as I got older the boys I’d played with for years began to peel away. Looking back, I see it was a social class thing. The crappy one-story house my family lived in, practically a trailer, was a blight in a nice part of town, and my clothes were hand-me-downs three times over from my older brothers. My father had a lot of different jobs and none of them made me proud. Let’s just say he never went to career day at my school to discuss being a garbage man. We were the trashy family down the street, which hadn’t mattered until it did. My last GA sponsor used to tell me to “make better memories.” How do you make a memory? Either you remember something, or you don’t. You can’t control its quality.

The meeting is in a dank social hall in the basement of a church. The overhead lights are fluorescent rectangles that are mostly working. A few are flickering, undecided. I take a seat next to a guy I’ve talked to several times, though his name is Czechoslovakian or something and I can never remember what it is. His pronounced overbite and protruding ears make me think of a chimpanzee, but his voice is as deep and melodic as a cello; it’s soothing to hear him talk. His story as I know it is he was a racetrack junkie, and his wife took his kids and left. His paycheck is garnished for child support now and he’s been trying to pay down a home equity loan that he squandered on the ponies.

“How’s it going?” I say to him.

“I made my final payment,” he says.

“Shit no,” I say.

He beams. “I’m debt free.”

I should be happy for him and to some extent I am, but I am mostly consumed by envy that he has left behind the consequences of his actions, and I still suffer mine every day. “That’s amazing, man. Congratulations.” I extend my hand and he shakes it.

“Anna says we can try again. Just dating for now, but she’s giving me equal time with the kids.”

“Soon your life will be back to the way it was before you gambled,” I say. “Wife, kids, friends…” Family trips and barbecues and surprise birthday parties. Most importantly, reliable sex.

“It’ll never be the same, you know that,” he says.

“Same enough,” I say sourly.

At the front of the room an elderly woman starts talking about the Powerball jackpot and how she used to play every lottery. “It’s tough,” she says. “I pass by a convenience store and it’s all I can do not to go in and buy a hundred tickets. That’s how many I used to buy, no more or less. I was superstitious about it. Oh my Lord, the rush I felt when they read the numbers on TV. I spent my whole social security check as soon as it came, and I never won more than two hundred dollars at a time. I’m itching to play for that jackpot tonight, I won’t lie to you about that, but I’m not buying any goddamn tickets, and I plan to be asleep at 10:59.” She raises her fist in the air à la Che Guevara and everyone applauds.

The chairperson gets up and asks if anyone else would like to share. I have shared maybe three times in as many years, but I spring up like a jack-in-the-box before I can think about what I’m doing and stride to the front of the room.

“Powerball!” I say. “I’m sick of the word.” There’s a grumble of assent in the audience. “What would you do with a billion dollars? Buy a mansion, move to the Bahamas? I even heard a guy say he would buy Microsoft!” I am warmed by their laughter. I’m a comedian now, an evangelical preacher, a politician on the stump. Sharing is fun; I should have done it more often. Problem is, I can never think of an interesting story: I have nothing new to confess. “I don’t want a billion dollars,” I go on. “You know what I want? I want two hundred nine thousand twelve dollars and eighteen cents. That’s my debt and I want to pay it off, is that too much to ask? Yes? No? I’ll tell you what else I want. I want to buy a house. Nothing fancy, just something with more than one room, because that’s what I live in now, a single shitty room.” I pause to gauge the audience’s reaction. I sense an uncomfortable stirring, disapproval in the air. It’s all about making amends and being humble with this crowd, not asking for anything for yourself. “I want a girlfriend. I want a new job. I want a dog. I want a vacation. I want the phone to ring and for it to be someone other than a debt collector or my mother. It’s been thirty-eight months since I last made a bet, and to tell you the truth, I was happier then.” This isn’t true, but right now I’m convinced of it. My old sponsor Howland Boyd is sitting two rows back. He moved to Indiana over a year ago and now out of the blue he’s here. I know all his facial expressions and he’s clearly not pleased. Fuck you, I think. Fuck you all. I thank everyone for listening and leave.

I drive to an outer suburb where the houses are new, and the trees are so small and spindly they’re stabilized by wires. They’re big houses and no doubt expensive, but their featureless concrete sides and backs belie their two-story front windows and pillared facades. In twenty years, when the trees are mature, these houses will be falling apart. I know a guy who lives out here, Joey Kinsey. We went to J. Fenimore Cooper together. He invented something that made him rich, a chip or an app, who knows. He’s pictured in the newspaper now and then at charity functions with his surprisingly unbeautiful wife.

It’s easy to get lost in a neighborhood where all the streets look the same. It takes me fifteen minutes to find a convenience store with a Powerball sign in the window. There’s also a sign for an ATM, which is great because I’m out of cash. I’ve never been here; I wanted a store where I hadn’t played before, and I’ve played at most of the stores around town. I wasn’t into the big lotteries so much, I only played if the jackpot was stratospheric, but I was obsessed with scratch-offs. I bought dozens every day. When you win a few bucks on a scratch-off, you don’t think about the thousands you’ve wasted. . Win or lose, you want to buy more scratch-offs, and around and around it goes.

The store and the gas pumps in front of it are lit by dinner plate-size lights, the chain link corners of the large parking lot look like daytime on a sad planet. Good luck to anyone who tries robbing this place. Security cameras everywhere. I pull into a space farthest from the store. I sideswiped some dickhead’s baby blue El Camino in a supermarket lot two months ago and I’m still jittery about my parking skills.

Just as I check the time on my phone, it rings. I wait several seconds before I pick up.

“Howland,” I say. “Why aren’t you in Indiana?”

“I’m visiting my mother,” he says. “What the hell was that at the meeting?”

“You mean what I said? Don’t worry, I was only blowing off steam.”

“Are you gambling again?”

“I’m not gambling,” I say. This is true. I am merely contemplating gambling.

“Have you gambled?”

“No, Howland. Not in three years.”

“Where are you,” he says.

“In my car.”

“Where in your car?”

“In the driver’s seat.”

He is silent and I think this means he’s satisfied by my answers. I’m a little chilly so I put the heater on low. The sand from the beach irritates my feet. Another car drives into the lot, its headlights strafing my windshield. It’s a white BMW, showy as hell. A medium height guy wearing chinos and a blue sport coat gets out. He turns toward me, and I see his face. I tell Howland I have to run.

“Joey!” I call as I get out of my car. I am driving a RAV4 that was my mother’s before it was mine; I’m hoping he won’t notice it. He stops and frowns as I run over to him.

“Do I know you?” he says. Then his face clears. He’s better looking now than he was as a teenager, but then who among us isn’t. “Lewis! Wow, I haven’t seen you since when?”

“Twelfth grade chemistry,” I say. “We were lab partners, remember?”

“I do!” he says as if he’s surprised. We spent a whole school year sitting next to each other pouring noxious chemicals into beakers, I would have been surprised if he didn’t remember. He claps me on my shoulder. “How’ve you been?”

“Great. You?”

“Great.”

We stand there with our hands in our pockets until he asks me if I’m going into the store. He opens the door and we both step in, he in his sport coat and me in my windbreaker. Nobody would think we were friends. I go to the ATM and take my time while he buys a pack of cigarettes.

“Listen,” he says after he pays. “You ought to come over some time. I live around the corner in Willow Estates.”

“I’d like that,” I say and hand him my phone. “Put in your number, I’ll text you.”

Because I don’t want him to see me play Powerball, I leave the store when he does and walk him to his car. I would like to crawl into its leather seats and be driven to his house, where I will be offered a snifter of some fragrant liqueur and invited to spend the night. I imagine his house looks over a lake though I know there aren’t any lakes in Willow Estates, only verdant lawns the size of miniature golf courses and trees that come up to my waist.

“Okay then,” he says, and gets into his car. I wave as he drives off.

I go back to the store and count my cash. The tickets are two bucks apiece. I can reasonably afford thirty. The guy behind the counter is gigantic, ridiculously tall and fat, and so dark his eyes are brilliant beacons, their whites as unsullied as milk.

“Hey,” he says as I stand there doing nothing, looking at the cash in my hand. I nod and say hey back. He asks if he can help me. I think a minute, chewing the inside of my mouth. Addicts fall off the wagon all the time. I can play once and start again. I tell myself I’m a hero for not playing for three whole years.

“I’m trying to decide on the Powerball,” I say.

He points at the clock behind him. “Too late to play.”

“Too late? No. It’s only five after ten.” I look at my phone to make sure.

He leans heavily on the counter, knocks his fist against his sternum, turns his head and lets go of a shuddering burp. It’s the most disgusting thing I’ve seen in a while. “We stop selling tickets at 9:59,” he says.

“Well, no one is looking, you can sell some to me. Rules are made to be broken, right?”

“It’s not a rule, it’s State law. You’re out of luck, dude.”

“I have to buy a ticket,” I say. “Just one.” Where I was undecided before, I am now ironclad.

He shakes his head. “Can’t do it.”

“Go fuck yourself,” I say in a voice that’s not mine, deep and gravelly, full of menace. I want to throw something breakable, but everything in the store is plastic.

“You better get out,” he says. “I have a gun back here.”

“Good for you,” I say.

I bang out the door like a pissed off adolescent. It’s a first for me, being kicked out of a convenience store. Not the lowest I’ve ever sunk, but the lowest since I quit gambling. I see the counter guy watching me through the filthy convenience store window. I flip him the bird with both hands as I walk backwards across the lot.

I get into my car and turn the key in the ignition. It starts, which it doesn’t always. I’m wondering if I can find a meeting around here. I have a story to share.