Toshiya Kamei

Sworn Brothers

At age five, I jumped onto our butler’s face, bit off his tongue and swallowed it. Warm liquid filled my mouth, salty and sweet, and he shouted incoherent curses, more blood bubbling from his lips.

My father scolded me until I swore I’d never do it again.

“You behave, young lady, or you won’t be a kabuki dancer,” my father said. “Is that understood?”

I nodded and stared at my feet. But the taste of blood lingered in my mouth.

It didn’t take much to convince the butler to stay. Tongueless manservants weren’t in demand elsewhere, and he didn’t mind sating my thirst now and then.

Aside from my penchant for blood, I had always imagined myself on the kabuki stage, even though no women were allowed.

My earliest memory was of my fathers dancing together, both dressed as maidens in robes of swan-like feathers. I must have seen a photograph of them somewhere, but no matter how many times I asked, my father denied the existence of any such image.

I climbed to the attic throughout my childhood and ransacked my father’s belongings, seeking evidence for my supposition: he had met his husband in Japan where they were both kabuki dancers. I perused old photos, letters, and postcards, but no clues emerged. His journal entries were scribbled in kanji, and I cursed my inability to decipher the characters.

Why had he gone to such lengths to conceal his past? Whatever the reason, he indulged me. He took me to his tailor and bought me a new suit whenever we attended a wedding or a funeral. I sometimes drew quizzical looks from other guests, but that didn’t faze me.

Everything was almost rosy. We lived in a white-columned mansion in upstate New York with the taciturn butler, and I was a boy. I never again bit off any tongues.

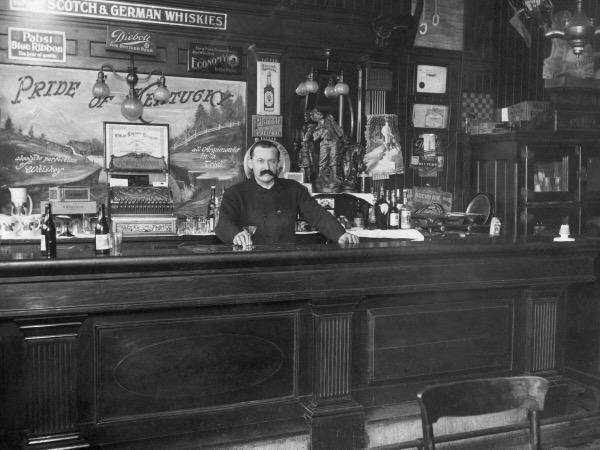

I went to Yale College in 1915 and lived in Connecticut Hall for all four years. In my spare time, I sought out Japanese men along the East Coast. I met high-ranking diplomats, royalty, and former samurai who wanted us to act out a scene from some Broadway play. Many were kabuki aficionados, and they told me about the performances they had attended in Japan.

“You remind me of an actor I saw in Yokohama,” one Tokyoite said. “He played Cio-Cio San in a kabuki adaptation of Madama Butterfly.”

The heroine’s tragic end made it impossible for me to fully enjoy Puccini’s masterpiece.

“You’ll grow butterfly wings and fly away someday,” he said.

It was with him that I learned my bloodlust, that long-ago desire that made me swallow the butler’s tongue, could be used for both pain and pleasure.

He handed me a leather belt and asked me to whip his backside.

“Ichi…ni…san…shi…go…roku…shichi…” I counted aloud, relishing each lash.

At first, he responded with a hushed intake of breath. As his skin broke, he roared with pleasure. He was as demure as a kitten once he attained ecstasy.

Long after his face became a blur in my memory, I still recalled his stale tobacco-tinged breath.

After the Tokyoite, I hurt more men who equated pain with pleasure.

And I soon found men who enjoyed being cut. Their blood ran in rivers down their reddened backs. It was dangerous—too intoxicating. Even so, I tasted the men who bled for me in my dreams.

Over time, I became attuned to the needs of my body and conversant in Japanese.

After graduation, I clerked in my father’s law office among well-dressed men who had recently returned from the European War. I wore my hair short and slicked back, a man’s tailored suit, and smoked a cigarette in a long holder. No one gave me a second look.

“Morning,” I greeted Betty behind the reception desk as I headed toward my father’s office. Her dress was patterned with swallowtails, which were my favorite butterflies.

“Hey, Angel, got a light?” Betty peered over her oversized frames. She held an unlit cigarette in her gloved hand.

“Sure.” I pulled the lighter from my breast pocket. When I leaned forward and lit her cigarette, her lavender perfume teased my senses. She blew a puff of smoke, and I swallowed. The fume made me recall the Tokyoite. The desire to bite stirred within me, but I held my breath and collected myself.

With a nod to Betty, I walked into my father’s office.

Seated at his mahogany desk, my father thumbed through a yellow manila file.

“What is it?” he said, barely looking up.

“Allow me to go to Japan, Father,” I said with a bow. I’d made this request countless times before.

“Angel, my boy,” my father said, fingering his mustache. “Do you still want to be a kabuki dancer?”

“Yes, Father.” I deepened my bow, my cheeks burning.

“I can’t change your mind, can I?”

“No.” I slicked down my hair with my fingers.

He opened his drawer and handed me a business card.

I squinted at the kanji. “It’s a boardinghouse in Yokohama!” My hands shook with excitement.

“Don’t lose it,” he said coolly.

He grabbed a pen and scribbled a note in Japanese. “Take this to Yukinojo Sakai. I saw him in Berlin on the last leg of his European tour, and he owes me a favor.”

“Thank you, Father!” I threw my arms around him and squeezed.

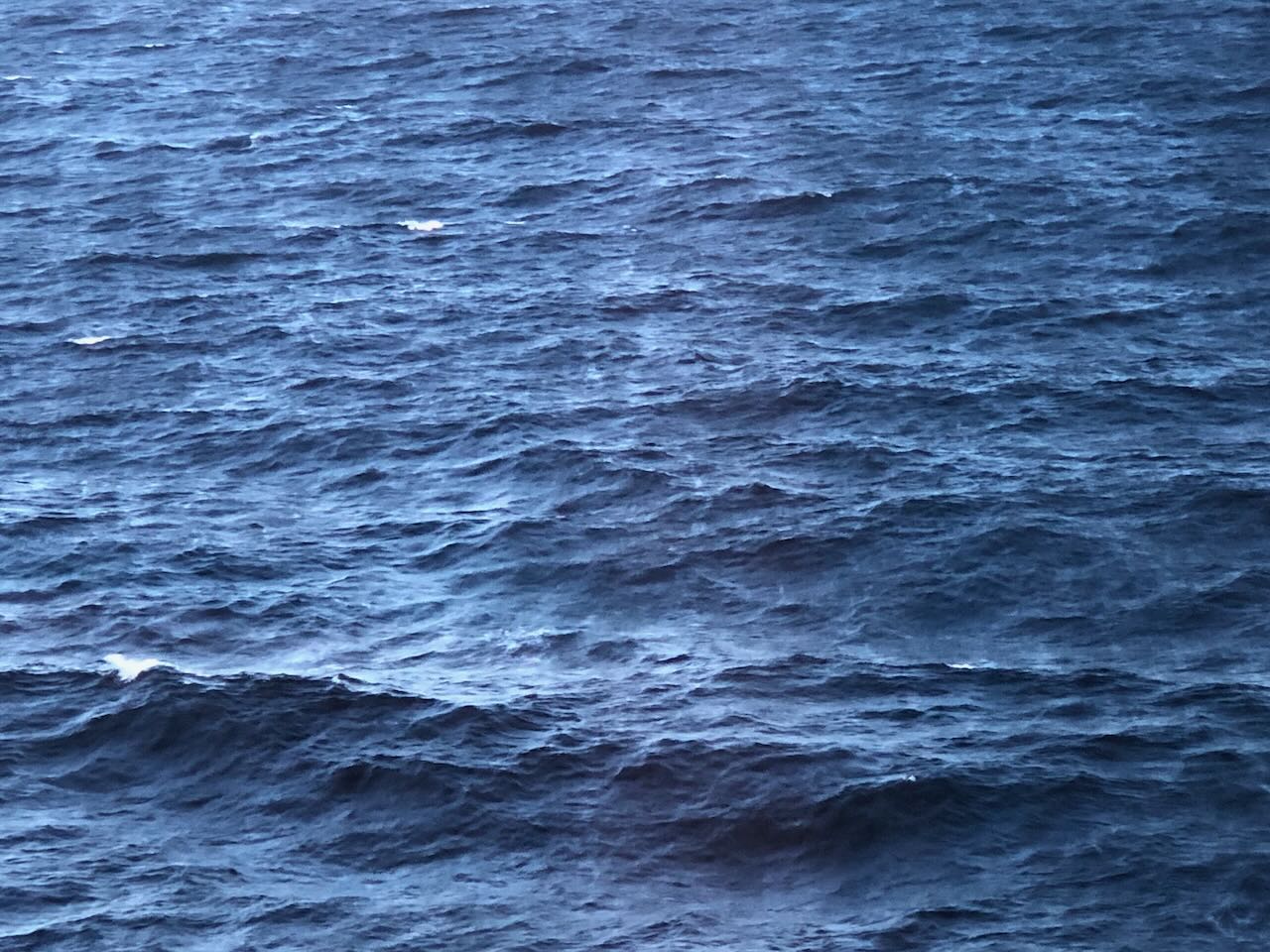

With the wings of that joy still fluttering, I set sail one week later. A strange and exhilarating journey ensued. Never before had I seen such brash sailors. My heart raced at the sight of their bronzed bodies. My gaze wandered over their white cotton fundoshi, which barely covered their groins. Now and then, I lured a sailor into my cabin and satisfied the urge to taste blood.

After two months at sea, we entered the port of Yokohama. As soon as our ship anchored, butterflies swarmed everywhere. Gossamer yet vibrant, some flew into the crowd while others glided overhead. Omens, surely, but what kind?

The docks bustled with sailors, pilots, and oarsmen from all over the world. As I walked along the crowded pier, myriad words and phrases, some familiar, grated on my ears.

White parasols bobbed along as the stream of people flowed past, some in Western clothes, and others wore kimono. Street urchins flocked around me, begging for money. When I searched my pockets for change, the first swallowtail landed on my nose. It was so beautiful. I couldn’t resist the urge to devour it.

I showed the business card to a driver and climbed into his rickshaw. His braided hair bounced on his back, and we sped along the track, chasing a cream-colored tram. Western-style brick buildings zipped past on both sides.

“Where are we going?” I asked.

He said something unintelligible in response. When we passed the red gate decorated with rows of paper lanterns, and storefront signs written in Chinese came into view, it all made sense to me. He was speaking Cantonese. Just like any American Chinatown. Around me, there spread a mixture of strange and familiar. It was my father’s way of looking after me.

The driver parked his rickshaw in front of a two-story brick building whose front was a pharmacy. My nose twitched at the unfamiliar scents of herbal medicines. We went around to the back, and a winding staircase spiraled upward.

“Thank you.” I shook the driver’s hand, handed him a coin, and sent him away. He muttered complaints under his breath. As eager as I was to explore the new surroundings, my body craved rest. The stairs groaned as I began my ascent.

When I reached the top, the rusty bell over the door chimed, and a stubby woman wearing a purple Tang suit with butterfly embroidery appeared and introduced herself as Madam Ng. The white powder plastering her face accentuated her ruby lips. Her clothes caught my fancy. I let my gaze linger a bit too long as I wondered how I could unhook the frog knots across her chest.

“You seem to like my suit,” she said. The lyrical lilt of her speech was enchanting.

I blushed.

“Maybe I’ll let you try on one of mine.”

Her faint floral scent wafted toward me, and I felt like sucking her blood.

We walked down the dark, curving corridor that seemed to last forever. When we reached the end, she ushered me into a single tatami room.

“Why don’t you come over sometime?” I tried to reach out, but she stepped away before I could touch her. She turned the corner and disappeared, and I was alone.

“Madam Ng!” I cried, but she didn’t come back.

A part of me was relieved. I decided to keep my distance until I no longer posed a threat to her.

Though sixty years of age, Sakai Sensei looked no more than thirty on stage. His kabuki diverged from what I had imagined. His was an all-male dance troupe with dancers dressed as women, and he tailored Western works to his audience’s distinct taste.

Fifteen trainees walked around to loosen their bodies, stopping in front of the full-length mirror and striking poses.

All the dancers were exquisite, but I took a liking to one in particular. His name was Kiemon. The quick grace of his movements enchanted me at first sight. I devoured him with my eyes.

“We’ll practice Swan Lake today,” Sensei said. “Watch me first, and then each of you will take turns.”

Dressed in a fine, transparent robe of swan-like fathers, Sensei transformed into a tennyo who descended from the heavenly realm. She dropped her robe on the beach and bathed in the sea.

Kiemon, a wide net slung over his shoulder, appeared as a fisher and hid her robe in her absence. The maiden danced for the fisher, pleading for her feathers. Tears clouded my vision. I stood speechless. I’d give everything to be half as good.

Following Sensei’s demonstration, we trainees took turns. The poignant storyline provoked a wide range of emotions like pity and sadness. I was the last to go.

My pulse quickened as I wondered why my father had been so secretive about his past. He had been here over two decades ago. Once a trainee like me, he had danced on this very floor. And here he had met his future husband and had fell in love with him. My other father. My dead father.

However much I tried, I failed to be a convincing celestial maiden. To my dismay, my untrained voice came out like a croak.

Sensei pulled me aside with a grave look. “You have a long way to go.” His words whipped me. “My standards are high. Your father trained here, too, and met the man he would marry—”

“What happened to them?” I fought to keep my body from trembling. I waited for him to say more, but he only grimaced before he left me there, confused.

After class, as I removed my wig and makeup at a dressing table, Kiemon sat next to me. When our gazes met in the mirror, we both nodded. I was the more masculine one.

As the rest of the class disrobed, I hid my bound breasts. When Kiemon caught me staring at his lean, sinewy body, he smiled. Later, I learned he was from a family of kabuki dancers, and that was the reason why he outperformed the rest of us.

“Let’s go to the sento and freshen up,” Kiemon said as he leaned toward me, wiping his brow with his sleeve.

I swallowed a gasp, even though I knew the locals weren’t too fussy about nudity. Men and women bathed together, after all.

“I still need to work on my movements,” I said, throwing up my hands. “Sensei thinks I’m a lost cause. He says I’m not feminine enough.”

“I can help you with that,” Kiemon said. “Watch how I walk. The trick is to exaggerate a little bit.” He feigned a shy smile and covered his mouth with his sleeve. “It’s easy, just copy me.” He walked across the room as if treading on fragile ice.

I nodded and did my best to imitate his movements as we left the studio together.

We stopped at a shrine on the way to Chinatown. We clapped and tossed coins into the offertory box.

“Make a wish,” he urged. I closed my eyes, clasped my hands together, and stood still. Butterfly wings hummed by my ear, and I opened my eyes.

“Do you want me to tell you what I wished for?” I asked.

“You’re not supposed to tell,” he said.

I contemplated this as we moved on from the shrine.

“Tell me about your family.” Leaves loosened from the tall trees around us and landed by our feet.

“I had two fathers, but—”

“Were they sworn brothers?”

“Sworn brothers?” I knew what he said, but the words sounded so foreign. So enticing. “What does it feel like to be someone’s sworn brother?”

“I’ve never been one myself, so I can’t tell you,” Kiemon said. He reached out and brushed my cheek. My heart fluttered.

“My father raised me alone,” I said. “His husband died giving birth to me.”

“I’m sorry to hear that,” he whispered, placing a hand on my shoulder.

I wondered what would happen if I let my tears fall.

With that, a somber air filled the space between us. We remained silent for the rest of the walk home.

I entered my building with Kiemon, and as we walked down the hall, Madam Ng emerged out of the corridor’s gloom.

“Hello, Madam Ng.” She wore a black cheongsam that hugged her curves. As she shuffled toward us, the slit in her dress opened and revealed the pale skin of her upper thigh.

“Who is your friend?” she said, looking us over.

“He’s my classmate.” Kiemon bowed. “Madam Ng is my landlady.”

“I love a fragile-looking flower,” Madam Ng said, licking her crimson lips. “I’d love plucking his petals one by one.”

I shot Kiemon a glance, but he didn’t see me. He was looking at her. His adoring gaze whipped me into action. I grabbed his wrist.

“I’m joking, honey.” Her purring voice followed us as I dragged Kiemon along. She said something else, but we turned the corner.

I led Kiemon down the narrow hallway, our sweaty bodies brushing against each other.

My room was hot, and it was hard to breathe. I grabbed an uchiwa and frantically fanned my clammy face. Kiemon tore off his sweat-drenched kimono, down to his fundoshi. Butterfly tattoos flurried across his back.

“That’s better,” he said, as if expecting me to follow suit.

I didn’t, though. I brewed tea and found something to nibble. Kiemon’s gaze stung me, but I didn’t know if it bore judgment or confusion. Did he know I was born a woman? Would it matter once he did? Would it matter to me if he did?

As these questions swirled around my head like a swarm of swallowtails, I bent to straighten Japanese textbooks on a low shelf, needing something to do with my hands. Kiemon came behind me. His bare skin pressed against my thin clothing.

“Let me show you the movements,” Kiemon said. I had no heart to push him away.

When he touched me to guide my movements, he lingered longer than he should have. My heart pounded in my ears, but I didn’t pull away. I knelt and pressed my mouth against his fundoshi. When I bit him, he cried out in pain. He begged for more.

After that day, he made a habit of coming to the boardinghouse. To my relief, he never broached the idea of going to the sento again.

Kiemon was also an expert shamisen player. One night, with a crescent moon high in the sky, he played for me. His delicate fingers caressed the strings, and melancholy stirred my heart. Swallowtails butted against the window as if they too wished to hear.

“Are you crying?” he said after he put down his instrument.

“No.” I tried to sniff away my tears.

He handed me his cotton tenugui, and I blew my nose. I knew I should give it back, but I wanted to keep it close to me.

Our gazes locked, and his brown eyes smoldered.

I leaned in and kissed him. I pulled away with a gasp, taken aback by my boldness.

But then, as I knew I would, I gave in to my desires. I could no longer resist Kiemon. He trembled as if he was waiting for me to seize control. I gently bit his tongue before gradually applying more pressure.

“Ouch,” he cried. My hunger raised its head, took a sniff, and craved more.

We kissed again, and the taste of his blood lingered in my mouth.

The seconds seemed to elongate. Each kiss made me shiver, and I couldn’t think straight. I could hardly breathe either, but I didn’t care.

“I’m exhausted,” Kiemon eventually said.

“Why don’t you spend the night here?”

“I’d like that.” He stretched his arms above his head and yawned.

We lay on the futon. I buried my face in his chest, savoring the rancid stench of dried sweat, and fell asleep.

That night, I dreamed of a dead butterfly. With my mouth full of pebbles, I screamed Kiemon’s name. I woke in terror, gulping air like a drowning man.

Kiemon clung to me, his body heat blanketing my back, and shushed me back to sleep.

The following week, he moved in. We vowed to be sworn brothers over cups of sake. I didn’t quite understand what our vows entailed, but I was heady with love.

“We’ll have more time to practice now,” he said, his laugh booming.

I was tipsy, and the lit lanterns spun overhead. My gaze caught his, the cocky spark in his dark eyes, and I mumbled he looked beautiful. Kiemon knocked his cup against mine with a grin. A little sake splashed onto the worn table.

“Drink up, brother.”

I couldn’t do anything but obey.

Madam Ng shot me an evil look when we passed her in the hallway, but paying double the rent settled the matter.

A month after we swore loyalty to each other, Kiemon and I tangled together on the floor. I sought Kiemon’s mouth and teased his tongue. But he pulled with a sad smile.

“What’s wrong?” I asked, alarmed.

“My fathers say it’s time I married my fiancé,” he said with a sigh.

At first, his words made no sense to me. And then the force of them crashed over me like a great wave.

“What?” I said, but he didn’t hear me. Annoyed by his vacant stare, I repeated, “What?” I repeated it again and again until my ears rang. Tears scorched my face. When he grabbed me, I wrenched myself free.

“He means nothing to me,” he said, dejected. “He’s just someone chosen for me before I was born.”

“How could you do this to me?” I shouted. “What about our vows?”

He winced, scrunching his shoulders to make himself smaller.

“I’m sorry, Angel. We can’t see each other anymore.” He shook his head and closed his eyes as if the dim natural light hurt him.

My mouth was dry and I struggled to form words. I briefly wondered if Kiemon and his spouse would take me as a concubine, but I wouldn’t allow myself to be debased like that.

Kiemon never looked back, not even once, as he disappeared from view. When I turned to go back inside, a single swallowtail fell dead on the step. I slipped its body into my mouth, but it tasted of ash. Heartbreak.

The following day, Kiemon was sent to his relatives in Ichikawacho, some ten miles away. I languished without him. I’d lost someone to wake me from my nightmares, so I stayed up all night. Sensei yelled at me about my sloppy movements, but every time I attempted them, the memory of Kiemon’s gentle touch struck me.

To distract myself, I asked Sensei about the past. About my fathers. But Sensei avoided my prompting by assigning me tedious tasks like sweeping the floor.

The more I missed Kiemon, the more determined I became. I cornered Sakai Sensei one afternoon after class. He had his back turned to me, and I hovered by his side as we swept. I wouldn’t leave him alone until I got what I’d come here for.

“Why won’t you tell me the truth?” When he still didn’t face me, I grabbed his arm. My hand trembled. “I didn’t come all this way for lies!” And maybe the desperation in my voice touched Sensei.

“I promised your father I wouldn’t tell anyone,” he said.

“Why?” My voice quivered with rage.

“He wanted to protect you.”

“From what?”

His face clouded, and he hesitated for a moment. “His husband was too pregnant to travel.” He averted his gaze. “Your father meant to come back.”

“But he didn’t!”

“No.”

“Don’t spare my feelings.” Tears ran down my cheeks, but I didn’t care. “Half-truths won’t do. My father abandoned his husband!”

“But he sent for you.” He sighed. “He might have failed his husband, but he loved you. He still does.”

After thanking Sensei, I walked until I found myself sitting on a bench by the shrine Kiemon and I visited the day we met. My emotions threatened to spill over. I loved my father, but I hated what he did. I was angry, yet relieved to know the full truth after so long. Above anything else, I wished my dead father was here with me. Of course, I could never speak that wish aloud if I wanted it to come true.

As time passed, I tried to numb myself to Kiemon’s departure and my father’s secret. I danced. I explored the city without a map, savoring the thrill of getting lost.

A few weeks after my talk with Sensei, I threw up and wondered if I was pregnant. Such a possibility was too cruel to contemplate.

The news of Kiemon’s death reached me days later.

“He fell ill and died from a broken heart,” Sensei said before class. A murmur spread among my fellow trainees, and I became unmoored. I saw myself from outside my body, disbelief making a mask of my face.

I needed to see Kiemon again. Maybe there was still a way to remedy all this.

“Angel, where are you going?”

Without answering Sensei, I ran outside and flagged down a rickshaw.

By the time I arrived at the cemetery in Ichikawacho, the sky had taken on an ominous hue. A lone swallowtail steered me through the endless maze of graves. A raven’s caw spurred my steps even as thorny shrubs pricked my limbs.

I stumbled and fell to my knees in front of the granite slab that bore my sworn brother’s name. The smoke from the burning incense stung my eyes. I tried screaming for Kiemon, but no sound emerged. I only swallowed more air.

I buried my face in the soil and devoured it. The fluttering of wings echoed in the distance, and I looked up.

Lightning zigzagged through the air and struck the headstone, splitting it in two and exposing his wooden coffin. The force threw me back. Blinded and seared into agony, my head rang with the terrible thunder clap.I couldn’t move or speak. My body lay broken beyond pain. But I saw him. Maybe it was a dream, but I saw Kiemon in front of me, a smile on his handsome face. Around him, swallowtails burst forth and flew in all directions. One landed on my lips and crawled into my open mouth. It stopped wiggling as Kiemon’s salty flavor returned with a final swallow.