https://cutleafjournal.com/content/no-call-loud-enough

April 2025

|

Poetry

|

D. Walsh Gilbert

No Call Loud Enough

Tooth Against Tooth

It was time she took the shielding muzzle off.

Inside, the ugly

cancer—a gargoyle beast— had come alive.

A hard button

of concrete had bared its chiseled teeth.

It bit

until there could be little sleep, a howling

demon,

an incubus fattening up on mother’s milk.

Since werewolves

are birthed after midnight, lusting for blood, she

slept outside

one summer night with a full moon shining

on her face.

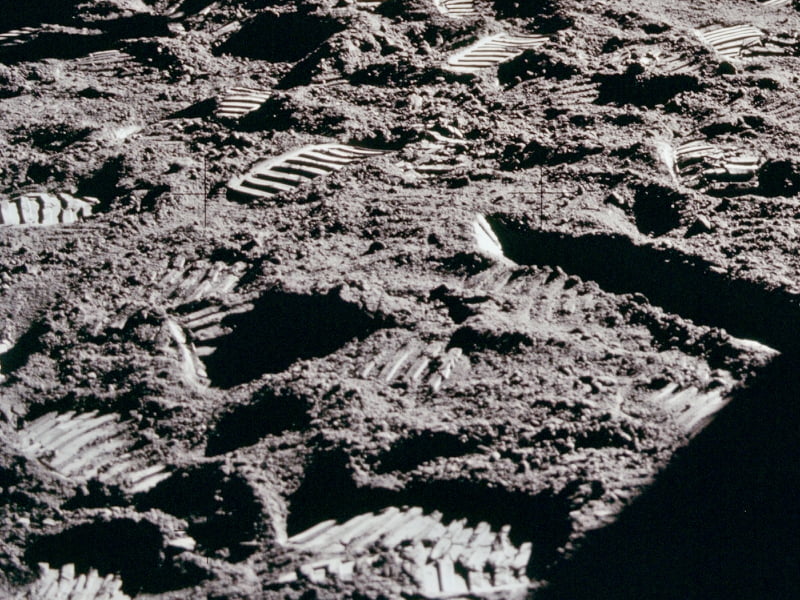

She drank rainwater from a muddy footprint

to become

that animal that devours—cursed, satanic.

She couldn’t wake

from canker’s nightmare. So, she bit back hard

—a wolf bitch—

tooth against tooth, a bare-knuckle fighter.

No Call Loud Enough

My mother was gone. I was driving home.

A red blaze burst from a broken window.

Gray smoke rose in the black night sky.

The backroad was silent in October’s autumn cold.

Mesmerized by bright flames, I finally pulled

the siren at the sleep-dark firehouse. It wailed.

Come, it called. Come quickly. Come now.

And the rescuers came, newly waked,

though too late to save the farmhouse

mercifully empty of child or hiding hound.

Just a charred shell like an orphaned daughter.

Helpless and distant in my green Skylark,

I mouthed, Hurry. I pled, Come back. Be sure.

But no embers lighted in the fallen leaves.

To 2040, and Jorie asks “what were u meant to pass on?”

Mother, may these letters reach you,

written on what could be

the fallen leaves kicked in October,

heaped until they’re burned.

My hands callus with the raking of them.

Given a second chance, I now see lies of omission

as self-promise, a beautiful betrayal.

Buried for too long, I picked up a shovel

to scratch aside the rocks and dirt, to search

for the terrier gone to ground.

This is the hole. The foundation

of the skyscraper built toward the stars.

You pocketed the city the way I wear the forest.

Its dogwood has replaced your guard dog.

I carve your name into an oak

and encircle it with a heart. Beneath the tree,

the shadows dim interrogation’s spotlight,

intensify forgiveness, and pin me to a land

free of concrete sidewalks where

morning glories exist beside the poison ivy, in peace.

A dragon took you, no fairytale about it.

Your princess was left

to become another skinned animal.

But we read the story’s end together,

the one where Gretel frees her brother,

the one where one mighty blow kills the wolf.

It all begins and ends with blood,

a mother’s delivery, then something scars

the tree bark. Sap flows. Sticky, but sweet.

Faster in the cold, and I am hungry.

I could devour tomorrow,

and you say, Let me teach you how to bite.