Phillip Hurst

In the Library of Shelved Dreams

All art is failure. A truism unfortunately true. Even masterpieces like Winged Victory or Hamlet or “Blowin’ in the Wind” are surely not quite as perfect, not as potent or tragic or stirring as what their creators had in mind when they crawled out of bed and began to chisel and scribble and hum on the harmonica. These artists are Emerson’s “children of the fire,” chosen ones charged with revealing the hidden truths of a reality that plays its cards strictly close to the vest. What underlies this lifelong and melancholy bargain is faith in the ideal—in the ideal as reality, in the conjuring of perfect form in this most imperfect of worlds—when lived experience shows us again and again that even the noblest of Platonic dreams will remain forever that.

And if what’s true for the children of the fire remains just as true for those of us who are mere kindling, then what of all those works conceived by the faceless and never-known? The Bible reminds us that many are called but few chosen, but that’s never made the many feel much better. More to the point, if all art is ultimately doomed to disappoint the artist, and therefore all works carry within themselves a seed of despair, what to make of those that fail more bluntly—not just in their creator’s secret heart, but in the everyday sense of simply never being noticed at all?

The friendly woman behind the front desk blinked in obvious surprise when I asked to tour The Brautigan Library. The collection was housed in the Clark County Historical Museum in Vancouver, Washington. After collecting my five dollar entry fee, she directed me downstairs. In the basement’s fluorescent silence, the squeaking of my Nikes on the pale tiles seemed unduly loud. The air was chilly, as if the thermostat were kept low to preserve the artifacts—a few hundred manuscripts shelved on low bookcases. These manuscripts were hardbound in dark covers of maroon or navy or black (a few merely sheathed in plastic) and they ran the gamut from phonebook-thick to volumes which might’ve contained only a few sheets of minimalist poetry. Tabs on the spines noted the year they joined the library, the majority between 1990 and 1994, as well as a subject matter heading. Among others, these headings included Humor, Spirituality, Meaning of Life, Love, and All the Rest, a categorization scheme referred to, nonsensically, as the Mayonnaise System.

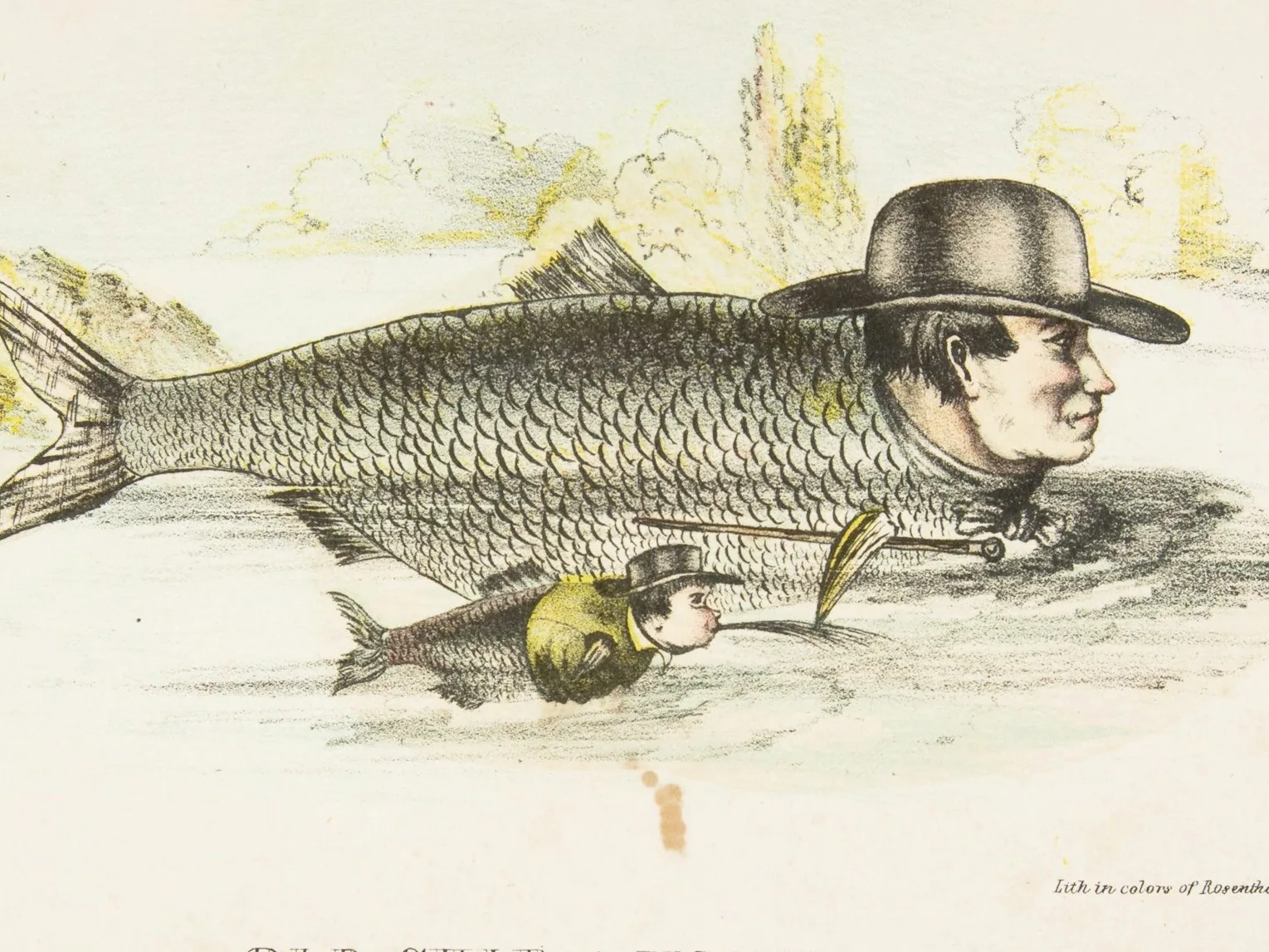

A few framed photographs of the library’s namesake—the late American writer Richard Brautigan—stood atop one shelf. In the first, a young Brautigan kneels in the grass while holding flower petals in the palm of his hand, as if offering them up to the viewer. He wears his trademark drooping blond mustache, round-frame spectacles, and soft-brimmed cowboy hat. In a second photo—the cover shot from his best-known book, Trout Fishing in America (1967), which famously and absurdly ends with the word “mayonaise” (sic)—he’s standing in a park in San Francisco before a statue of Ben Franklin. Brautigan is stork-legged and narrow-shouldered, clad in a vest and long-tailed jacket. Between the hat, the mustache, and the retro attire, the resemblance to a six-foot-four Mark Twain is unmissable, as was the image-conscious author’s intent.

In 1971’s The Abortion: An Historical Romance 1966, Brautigan imagines a library exclusively for unpublished manuscripts. In a postmodern twist, a character named Richard Brautigan shows up in The Abortion and submits his own aborted manuscript (titled: “Moose”) to the library. Brautigan modeled this imaginary library on the Presidio Branch of the San Francisco Public Library, even using the real address in his fiction, the result being that for years after The Abortion was published the library received requests from failed authors hoping to submit their own books.

Then, a little over five years after Richard Brautigan’s death, a man named Todd Lockwood decided to make the fiction real and founded The Brautigan Library in Burlington, Vermont. Lockwood was inspired by the 1989 film Field of Dreams, where Kevin Costner plays an Iowa farmer compelled by visions and voices (“If you build it, he will come . . .”) to mow down his cornfield and erect a baseball diamond. In 2010, the collection was moved to its current home, where I found it, in Vancouver. And a fitting move it was, as Brautigan was born and raised in the Pacific Northwest.

Per Jubilee Hitchhiker: The Life and Times of Richard Brautigan—a massive biography which his close friend William Hjortsberg spent two decades compiling—Richard Brautigan’s was an impoverished and lonely childhood that began in blue-collar Tacoma, Washington in 1935. Raised by a single working mother, Brautigan was tasked with raising his younger sister, and together they often resorted to gathering and selling berries to neighbors for grocery money. When that failed, they fished and jigged for frogs. Eventually, the family relocated to Eugene, Oregon. As a teenager, Richard Brautigan was a loner, a skinny boy who played no sports and never even learned to drive. But he did begin writing, poetry mostly, although he greatly admired Ernest Hemingway. Later, friends would describe Brautigan as obsessed with Hemingway’s death, claiming he’d memorized every detail of Papa’s messy goodbye, from the date and hour to the model and caliber of the firearm. In fact, Trout Fishing in America contains a chapter where the narrator finds himself near Ketchum, Idaho, “just after Hemingway had killed himself there . . .”

A few years after graduating from Eugene High School, lovesick over a young girl, Brautigan chucked a rock through the window of a local police station. In light of his odd behavior, the authorities shipped him up to Oregon State Hospital at Salem. OSH is the same hospital made famous by Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and the Oscar-sweeping 1975 film adaptation. In quite the literary coincidence, Kesey actually grew up in Springfield, just across the river from Eugene. While the two writers never met as kids, they later became drinking buddies, with Kesey prophesying that in five-hundred years when all the other writers of their generation were forgotten, “they’ll still be reading Brautigan.” But while Kesey wrote fiction about OSH, Richard Brautigan’s experience there was nonfiction. After his psychiatrists listened to their newest patient declare himself a genius, they wrote on his commitment papers that he “had the delusion that he was a writer of great ability.” The treatment for such literary delusion? Twelve separate rounds of electroconvulsive therapy in a single month.

Satisfied they’d cooked the poetry from their young patient’s brain, Brautigan was discharged shortly after his twenty-first birthday. He left Eugene for San Francisco soon after. Neither his mother nor his sister ever had any significant contact with him again.

But I hadn’t come to the library solely out of interest in Richard Brautigan. I had reasons more personal, reasons having to do with my own trove of unpublished work, one that’d been growing for well over a decade—a four-hundred page novel with its booted feet firmly in the incinerator, and a once-promising travelogue recently transferred from ICU to hospice, not to mention two or three other books committed to the Cemetery of Doomed Drafts.

One lesson you learn as a writer, though, successful or otherwise, is that everything is ultimately grist for the mill. And don’t forget that old pearl commonly foisted upon young writers—write about what you know best. Considering I could no longer reasonably think of myself as a young writer, it had become apparent that the one thing I knew quite well was literary failure. Though I wasn’t interested in adding my own work to the collection, it seemed the books interred in The Brautigan Library—many of which cost their authors no less effort than books that became bestsellers—deserved someone’s attention. Hence my plan to choose one unpublished book, more or less at random, and read it cover to cover. To read this book as I would any published book: not as an oddity, but with presumptive confidence in the author’s intelligence and heart.

The first volume plucked from the shelf (Social / Political / Cultural) turned out to be a play based on an affair between the Anglo-Irish revolutionary Maude Gonne and W. B. Yeats. Interesting, but I was in the mood for prose. The next candidate (from All the Rest) was a series of meditations written by a Chinese author from Oakland. Dense blocks of text ran for hundreds of pages, the author’s staccato clauses subordinating and folding back upon themselves in ever more convoluted wrinkles. After a few minutes, head reeling, I admitted defeat. Another book from the same section was an account of a cross-country motorcycle trip in the vein of Blue Highways, complete with hand-drawn illustrations and prefaced by a touchingly supportive note from a friend. But this failed travelogue struck a little too close to home.

In the Meaning of Life section was a manuscript authored by a husband and wife team from Omaha, a sort of Midwestern Fifty Shades of Grey, full of cuckoldry and cunnilingus. This was fitting actually, as Richard Brautigan never shied away from writing about sex. In fact, many of his poems find their subject in his own fleshy protuberance (“Pissing a few moments ago / I looked down at my penis / affectionately / Knowing it has been inside / you twice today makes me / feel beautiful.”). Nevertheless, I felt a tad reluctant to spend the day reading soft-core porn in the basement of the Clark County Historical Museum.

In the Humor section was an anonymous volume that’s introduction bemoaned how, during the Reagan-Bush era, it was hard to feel good about doing anything except for trying to hoard money. While certainly relevant, this was far too depressing. The book I finally settled on was from Love. A slender volume bound in handsome dark plum, its onion skin pages were so brittle I feared they’d rip with each delicate lift and turn. The author was from Missouri, which caught my attention because my late father was born in Missouri. A writer himself (he’d studied journalism and later published a small-town newspaper), my father was also a staunch believer that his youngest son—i.e., me—was no writer, as well as a frequent and vocal advocate of that son’s inevitable literary failure. And the old man was apparently right, at least in the conventional sense of recognition and money. Not that he understood the dynamics of modern publishing, the abysmal odds and bean-counting gatekeepers. All my father knew for sure was that money was all that mattered. Thus, with the exception of James Patterson and Danielle Steel, there were no writers in America (besides small-town journalists, of course) who might call themselves a success at all. But his was an easy attitude to take. After all, the odds of striking it rich writing books are more than slim, and that’s even truer now than in Richard Brautigan’s day.

The point of this trip wasn’t to reminisce, though. No, I’d come to The Library to read the work of one of my fellow failures, a comrade in disappointment who, unlike Richard Brautigan—a writer who briefly became a national sensation and whose odd little poems and quirky novels sold millions of copies—failed so thoroughly as to remain completely unknown. So I got down to it. The Missouri author’s unpublished novel began with some nice pastoral description. A typo was corrected charmingly by hand. Soon, however, the story turned to fishing—trout fishing—and by the time a strand of guts were described as a “fish abortion” I suspected I’d stumbled upon a homage to the author of Trout Fishing in America. These suspicions were confirmed when the young male narrator and a whimsically beautiful blonde get inexplicably nude and cavort in nature. A hippie fantasy ensues, with the blonde shedding her clothes four separate times by page twenty-eight, and the narrator writing poetry by moonlight, almost as if he is Richard Brautigan.

San Francisco during the late 1950s had a rich literary and countercultural scene, mostly centered in North Beach, and Richard Brautigan quickly infiltrated it. In time, he would come to be known as “the last of the Beats,” but Brautigan was never really part of the Kerouac-Ginsberg-Cassady phenomenon. In fact, Allen Ginsberg derided the tall young poet as a neurotic creep. But those who knew him best described Brautigan as charming, a guy capable of great sensitivity and sweetness. Having made friends in literary circles who were less judgmental than Ginsberg, he began to publish.

His first poems appeared in 1957, the same year as On the Road. Noting the success of that book, Brautigan switched to prose and began sketching out the chapters that would become Trout Fishing in America. These included a lot of banal observations turned weird, as well as “found art” whereby Brautigan included little notes stumbled across in daily life. The book lacked a through-line, however, with Brautigan ultimately structuring it around an extended fishing trip through the Northwest with his wife and newborn daughter. One wonders if this wasn’t inspired by the Beats, as well, considering all of Kerouac’s thinly-fictionalized road trips. Being a Hemingway fan, Brautigan was also familiar with A Moveable Feast. Whatever its origins, Richard Brautigan fantasized that Trout Fishing in Americawould launch him to literary stardom, as he’d witnessed with On the Road. And amazingly enough it did exactly that. Between Brautigan’s canny self-promotion as the quintessential hippie writer—though he personally disparaged the hippies—and a growing personal legend that included Please Plant This Book, a pamphlet of hand-printed poems complete with seed packets, Richard Brautigan found himself a ’60s icon synonymous with Haight-Ashbury and all things groovy, turned on, and tuned in.

In time, Trout Fishing in America would sell over two million copies and be translated into languages all across the globe. The book’s reach extended even farther, as a pair of Apollo 17 astronauts named a moon crater “Shorty,” after one of the novel’s more memorable characters. Brautigan enjoyed his newfound celebrity, touring the country via handsomely paid reading gigs, and seeing one book after another published to wildly ballooning advances—if also to increasingly tepid reviews. He drank whiskey with Jim Morrison and Janis Joplin, fished with Rip Torn, made friends with Jimmy Buffett (pre-Margaritaville) and Peter Fonda (post-Easy Rider), ripped up a pile of money in a bizarre encounter with Jack Nicholson (Nicholson kept the shredded cash as a memento), and purchased both a drafty old house in seaside Bolinas, California, as well as a spread near Livingston, Montana where summers saw him drink and carouse and shoot guns (often as not indoors) with literary heavyweights like Tom McGuane and Jim Harrison, to whom Brautigan once loaned $5,000—a year’s pay at the time—so that Harrison could write an early novel of his own.

But there was a dark side to Richard Brautigan’s spectacular ascendency, and friends worried about his heavy drinking and erratic behavior. As the years passed, Brautigan grew obsessed with money, an ironic departure for the godfather of hippie literature. He fantasized about Hollywood millions, while what money he’d already made he invested poorly or not at all. A divorce took a big chunk, and as the 1970s wore on the books stopped selling. Brautigan soon found himself almost as poor as he’d been growing up in the Northwest, but now having acquired expensive tastes (Pouilly-Fuissé, Tokyo hotel rooms), alimony payments, and tax bills in multiple states. He drank like one of his own trout, grew a pot-belly, contracted a nasty case of herpes (which perhaps inspired “Flowers for Those You Love,” a poem about venereal disease), and nursed a fetish for handguns.

A week prior to my trip to The Brautigan Library, on a slammed Saturday night at the bar where I worked—the latest in a long series of bars—I’d been hunched over the dishwashing machine, my thrice-reconstructed knee howling, washing rack after steaming rack of glassware, when my phone vibrated in my pocket. I turned my back to the thirsty crowd and checked the new email.

Dear Author,

Thank you for your proposal regarding “The Land of Ale and Gloom.” Unfortunately . . .”

This in regards to the previously mentioned travelogue, from the press I’d felt I had the best shot with. The rejection letter gave no sense as to what turned them off, and so—like all the other rejections—it wasn’t even useful criticism. I’d been waiting on this response for eight months, though, a not unusually long wait in the perverse timescales of American publishing, but a long wait indeed for a writer desperate to finally see print. This desperation wasn’t so much financial (I had no illusions of becoming the next Richard Brautigan), but instead owed to the passage of time. Because one less-discussed aspect of literary failure is how abominably long it takes. Yes, we have Chaucer (“The lyfe so short, the craft so long to lerne”), but still—it’d be one thing if a writer could fail in short order and move on, but to fail thoroughly and properly takes decades.

First, one must learn the craft sufficient to even attempt something original, which is a process of mimicry and falling short that takes years and years. Concurrently, one must read everything it’d be shameful to be caught not having read. Often, and as was the case with me, the foregoing involve attending an MFA program, a two or three year fandango of cheap booze and snide critiques by which the student slowly comes to understand he’s been snookered into a pyramid scheme whereby the hopes of young writers are used to subsidize the careers of older writers whose writing doesn’t actually make any money.

Beyond this point, it’s possible the aspiring writer has attained sufficient life experience to have something actually worth saying, but if not they will simply have to wait. Once properly seasoned, the writer must then spend years writing his or her actual books, editing those books, editing those books again (and again, and again), before undertaking a months or even years long fishing excursion for a literary agent—an excursion which in all likelihood will only convince the writer that literary agents are a species of trout too slippery to be caught. It may even come to seem these agents have themselves only read one book, Catch-22, and somehow mistaken the satire for a business manual: hence a model whereby writers must first convince the agent to pitch their books to Big Publishing—with Big Publishing happy to use agents as unpaid slush readers—but with an understanding that no writer who hasn’t already published with Big Publishing will be deemed suitable to be published by Big Publishing.

It takes a while to wrap the head around all that. Then it’s on to the small presses, where another year or two is spent researching, querying, drafting proposals, and being sent form rejections by publishers who state upfront that they can’t afford to pay anything beyond a token anyway. And finally the kicker: even if a writer does manage to land a deal with an indie, it will be at least a couple years from that point before the book actually gets published. The upshot? A living, no matter how meager, will not be made, much frustration and anxiety will accrue, and the writer will awaken to wrinkles in the mirror and the realization that they’ve egregiously misspent somewhere north of 20,000 hours of their youthful efforts—efforts which apportioned differently would’ve surely resulted in a 401k and sick leave. Maybe even dental.

Finally, the writer will realize that, all along, they had reason to know. The statistics on how many writers actually make a living in America are simply appalling. Groups like the Author’s Guild regularly publish studies which show that nearly every writer in America is also teaching classes or hustling seminars, driving for Uber or waiting tables. Almost nobody is living by pen alone, and this is hardly breaking news. After all, Melville died broke and thinking himself a failure. It wasn’t until he was dust and bones that lit departments began to wonder if all those crummy reviews of Moby-Dick might’ve been off the mark, with Big Publishing then swooping in to make a killing.

This is far from the only example of its kind, of course, and the lesson no secret. Hjortsberg, the author of Brautigan’s biography, won a prestigious Stegner Fellowship at Stanford, and he relates a conversation wherein Wallace Stegner was asked how many of the fellows actually end up earning a living. Stegner’s reply: “Young man, you don’t understand. You’ve chosen a profession that doesn’t exist.” In this sense, beating yourself up over literary failure is not unlike feeling bad for failing to strike it rich as a professional thumb-wrester.

What does it mean then to be forty-years-old and finally bereft of illusions?

Such brooding would have to wait, though, as The Brautigan Library closed at five and I needed to finish the Missouri novelist’s failed novel. As it turned out, the blonde is a poet just like the narrator, and soon she’s feeding her dashed-off poems to the trout in the stream behind her cabin. Then a blue cat shows up and begins reciting verse of his own. This shortly before the narrator finds himself in a cave, which is not unlike a rabbit hole, and so the book’s influences resolved: Richard Brautigan lost in Wonderland if the Cheshire Cat were a Beat poet and Alice a foxy nudist and expert angler.

This sounds silly, but many novels sound silly with their contents flatly stated.(1) Consider the works of Richard Brautigan, for example. Early in Trout Fishing in America, the narrator gets into a cussing match with an outhouse. Later, the eyes of a bookstore owner are described as “like the shoelaces of a harpsichord.” Another of his novels that sold by the truckload, In Watermelon Sugar, reads as if Hemingway were trying his hand at YA magical realism after one too many daiquiris. The story takes place in a fantasy world subtly named “iDEATH”, and the reader is informed that talking tigers ate the narrator’s parents before helping him with his math homework. Finally, an authorial coda states the novel was written over a span of just two months. Not to condemn Richard Brautigan’s writing entirely. There’s a disruptive playfulness in the best of his language, and the image of a dissembled trout stream—it’s sold by the foot length, and while birds and deer are extra, trout are included—is squarely in the wheelhouse of the Lost American Pastoral, with shades of Whitman and Thoreau and Melville.

Then I heard footsteps coming downstairs. Could there possibly be someone else interested in all these unwanted books? But it was only the woman from the front desk. We avoided eye contact as she slipped past and then softly closed the restroom door. (Have I neglected to mention the Brautigan collection is jammed into a corner near the public toilets?) I’d just returned my attention to the Missouri manuscript—the narrator was being assailed by some sort of flying chicken witch-monster, reminiscent of those winged monkeys from The Wizard of Oz—when my reading was interrupted by the echoing thunder of the desk-woman’s stream. Richard Brautigan’s daughter, who did the honor of placing the very first book on the library’s shelves, has stated her father would’ve loved the archive, and listening now to that plashing crescendo, I was inclined to agree. He would’ve delighted in the oddity and whimsy, the offbeat attitude. But one thing Richard Brautigan would not have loved is seeing Richard Brautigan’s own books shelved there amidst that chorus of failure, had it been his fate to remain similarly obscure.

Because while he’s lumped in with the hippies, and though he engaged in eccentric projects like Please Plant This Book, Brautigan clearly understood that the soul of America is made of cold, hard cash. That’s why he so carefully curated his image, meticulously staging those seemingly spontaneous photos that grace the covers of his books, and that’s why he dreamed of million dollar Hollywood paydays. Like Twain, he worried a lot about money; also like Twain, he squandered most of what came his way. And then there was his idol, Hemingway, who married well and spent lavishly. All of this yearning after wealth and the fame is, of course, ancillary to the act of writing, to creating with language. Outside validation. Externalia. Not the thing itself, not being, but having. Then again, people often say that money is the only way we have to keep score, a dictum at once colossally stupid but also stubbornly difficult to argue with.

In “The Poet,” Emerson writes of how we need to tell our truths, to give voice to the world as we see and feel it. “The man is only half himself,” he writes, “the other half is his expression.” This raises one possible escape route from the gulag of literary failure. We can strive to be wiser than writers like Richard Brautigan and aim not at wealth and fame, but at something more personal and lasting: self-expression. And this seems partly the purpose of The Brautigan Library. It’s not about commerce, but creative outlet. In this light, self-publishing might work similarly, assuming one can resist dreaming their book will break out like the aforementioned Fifty Shades of Grey (which had origins as sexed-up Twilight fan fiction). Whatever the case, with the right mindset an ISBN on Amazon or a slot in The Brautigan Library might prove a far better bargain than years of writing unacknowledged queries to literary agents and small presses. Better yet, we might not need to publish at all. If self-expression is the whole point, than a sturdy journal should do the trick. In fact, what’s to stop us from simply committing our morning writing to the backs of old grocery sacks and then burning those Zen scraps in the yard come dusk?

Yet it does seem that self-expression oftentimes presupposes some sort of audience. After all, the empty room makes for lonely conversation, and so we have to ask—is expression thereby void? And if a person really is only half their self without their words, and if here in America we are what we do, which seems the consensus, then what happens when we’ve put all our eggs into the writing basket, and we’ve tended that basket carefully, only for nothing to hatch? If midway on the path of life I discover I’m not this writer I’ve long been telling myself (and others) I am, then who or what am I? What to make of this seemingly dreamless and directionless next forty years?

Such thoughts had distracted me from the novel open on my lap. I ran my fingers over the onion skin page, admiring the decades-old ink. Then I glanced around at all those forgotten books. I could feel the dreams contained therein, the weight of their bundled psychic energy, the hope and frustration and the moments of private triumph when something wholly new rose, the elegant line or unique metaphor, and made that miraculous leap from heart and brain to the moving pen or typewriter keys. I took a breath and felt part of that brotherhood and sisterhood of failure—a bleeding out of faith in a world that’d merely shrugged at these gifts we’d so sincerely offered up.

Of course, it’s also possible our books just weren’t very good. Let’s not discount that. Or maybe they came at the wrong time, or failed to find that one sympathetic reader. Or maybe, like Wallace Stegner said, one shouldn’t expect any different when pursuing a profession that doesn’t really exist. There might even be a certain freedom in that, a release from crude assumptions—but for the invisible hand of capitalism wrapped so tightly around writers’ throats.

A not inconsiderable amount of the pain of literary failure stems from this tension between vocation and avocation. We writers want a life, as Frost puts it, “where love and need are one / and the work is play for mortal stakes.” But again, we’re not making much money and it’s hard to muster the energy to write after working nine hours, grocery shopping, and changing the cat litter. Here we run headlong into that dread word—hobby. Because beneath this seemingly innocent term lies much emotional pain. A hobby? Not a calling at all, just the scribbling of an embarrassingly overambitious diarist? The writers I’ve known want, perhaps more than anything, to matter. Money would be nice and the lack of respect stings, but the real killer is our words not mattering. Not to anyone. Then again, maybe success would ultimately solve none of that?

Again, consider Richard Brautigan. His fame fading, he’d been spending time in Japan, wandering the streets and writing poems before getting plastered every night in the same bars. Eventually, he met a pretty Japanese woman. She was married at the time, but he quickly stole her away, only to declare to his new bride that he would never live to see age fifty and that she was to cremate his remains and flush them down the toilet. Full-bore alcoholic, his books panned by critics who’d resigned him to the dust bin of 1960s, Brautigan’s behavior grew weirder and ruder—his drunken abuse once caused a notable Japanese film director to shatter the author’s nose with a karate chop—and yet also more worrisome, as he actively spoke of suicide to anyone who would listen. Literary success had brought no lasting happiness, not even when coupled with a fortune, and perhaps this illustrates one of the problems all writers face: the belief that if they could finally just get over the hump and publish, then all their problems would melt away. That all those years of discontent could be shed like a shabby old coat. But then an occasional writer like Richard Brautigan really does grab the brass ring, only to awaken the next day to all the familiar miseries.

The problem here for the unpublished, however, is that by never getting over that hump, they never learn this lesson, and so they lumber on, encumbered by a naïve hope that their dream life really is just around the next New Releases display case at Barnes & Noble. And let’s not forget the world’s assumptions. Picture a hypothetical real estate developer who’s hit a rough patch. People might say he’s had a setback, or even that he lacks a head for business, but even if he goes bankrupt they don’t call him a failure. They assume he’ll either land the next deal or switch careers, whereas the assumption for the writer is that he or she will die in a filthy garret and be wheeled out to the recycling bin. Because even those who don’t write and cannot write sense in the act some inextricable link between the writer and his or her words, and they hate us for possessing the imagination and courage to fail so boldly.

Seen in this light, maybe The Brautigan Library provides a valuable service, insofar as it gives the unpublished a sense of (forgive the expression) closure, thereby granting them a chance to accept that, though love and need may indeed be one, their real work is not creative play—it’s actually just their nine-to-five—and therefore is not and never will be for the mortal stakes of art.

The Missourian’s novel wrapped up nicely enough. While it wouldn’t impress the John Gardners of the literary aristocracy, it did its job. The narrator, with the help of the beautiful hippie blonde and the blue cat-poet, finds the courage to confront his inner demons down in the underworld, as Odysseus and Dante’s Pilgrim did before him, as Jesus Christ did and as Bruce Wayne did, and upon returning to the light he’s a bettered man. Also, the story’s near-constant nudity finally results in a much-anticipated merging of youthful bodies and souls.

I closed the book and returned it to the shelf, enjoying that mysterious moment which lingers after a story’s final page, that bittersweet return from other realms. I wondered about the author—where he was now and if he’d written other books, if he was still alive at all—but this only got me thinking about his inspiration. Richard Brautigan’s narrator in The Abortion describes himself as “not at home in the world,” and the author couldn’t have described himself any better. From his poor childhood in the Northwest clear through his meteoric literary rise in San Francisco, Brautigan had been an outsider, as perhaps all writers are outsiders, and he paid the price for exploring that territory. The man who’d spun fringe-fame into one of the more lucrative and colorful literary careers of the twentieth century ended his own life at the house in Bolinas in the fall of 1984. As relayed in excruciating detail by Hjortsberg (seemingly in hopes of draining the glamour from authorial suicide), Richard Brautigan loaded a .44 magnum with hollow points and tucked the barrel under his chin, before taking one last look at the sand and trees. His body lay undiscovered for a month. He’d done it near his writing desk and his blood and brains covered a pile of unfinished manuscripts. He was forty-nine-years-old, his prophecy self-fulfilled.

Despite rumors to the contrary, Brautigan left no suicide note, although in retrospect his books themselves read like goodbye letters. In addition to the prominent mention of Hemingway in Trout Fishing in America, that particular book is full of death images, graveyards and tombstones and even a gothic scene in a hot springs where the narrator and his wife make love in a tub full of rotting fish. Death ideation is even more pronounced throughout In Watermelon Sugar, which has doom imagery on nearly every page, and features not only the suicide of the narrator’s ex-girlfriend, but a mass suicide of drunken cult members. I find it all hard to read, frankly, and weirdly at odds with Brautigan’s public persona as the peaceful writer of the Summer of Love—so much so that one wonders how many of those millions of copies of his books actually got read.

Before heading back upstairs and bidding goodbye to the friendly desk woman, I took a last look at that singular photograph, the one of a young Brautigan offering up a handful of flowers. If he really had embraced the hippie philosophy—as opposed to obsessing over money and trying to out-macho Ernest Hemingway—maybe things would’ve turned out differently? Such supposition isn’t really fair, though. On the topic of Brautigan’s death, Jim Harrison described a chicken-or-egg scenario, unsure whether his friend was a writer who became a suicide or vice-versa. Still, sitting alone in the fluorescent chill of The Brautigan Library, surrounded by manuscripts that were loved and nurtured and brought into the world only to find no breathable air, I couldn’t help but wonder whether Brautigan’s quintessentially American success didn’t also hasten his undoing.

Turns out the author of the manuscript I’d read was still out there and still writing. According to his bio, he’d worked a lot of interesting jobs and traveled the world. He’d been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and now taught creative writing. He was married and a father. Thinking of Richard Brautigan’s sad life, I sensed the proper lesson in all this, but old dreams and old habits die hard. In the weeks to follow (even while drafting this essay), a fantasy germinated in the back of my mind, the gist being that while writing about literary failure and unpublished manuscripts, I would finally receive the call from a publisher that would save me from my own subject. I’m not exactly sure how I would’ve treated this on the page, but the idea was there, fainthearted as it now sounds.

I was back home in rural Illinois visiting my mother when I got the email.

Dear Writer,

Thank you for submitting your proposal. Upon review, however…

This from the final publisher who it seemed I had any real chance with. After reading the email again, I told my mother I was heading out for coffee, then walked to the home of a childhood friend. There in my friend’s garage, fading daylight trickling through the small windows, I commenced to drink in earnest. I didn’t tell him why, didn’t breathe a word about my writing or the parade of rejection. Instead, we talked about the old days while carefully avoiding any mention of my career prospects, which at one time must have seemed bright. My friend wisely gave up on keeping up somewhere around the tenth drink, as mine was the sort of drinking intended to obliterate consciousness, not merely to numb the emotions but to obliterate even the possibility of words. The rest of that night is lost, naturally, but I awoke the following morning facing the same realities. And as a writer (even a hungover one), I did what comes most naturally: I read.

In particular, I turned to Emerson, that almost preternaturally confident voice. Emerson argues the universe is the soul made manifest, that nature and the world answer to a moral power, and in my disappointment it occurred that—though this universe obviously cares for us not a lick—I’d been living along the lines described, at least in terms of writing. But reality and culture don’t respond to faith. Nor do they necessarily respond to hard work, talent, or good intentions. This in sober moments I understood. But maybe rational intellect doesn’t always have the final say? Because in his belief that the true poems of America are as yet unsung, Emerson concludes that a set of hard but equal conditions define a writer’s life: first, the price demanded, “that thou must pass for a fool and a churl for a long season;” and second, the reward, “that the ideal shall be real to thee.” Put another way, unless a writer gets as improbably rich as Richard Brautigan, everyone will think they’re wasting their time, and their only real reward will be some vague notion of an idealized world.

The upshot here is that chasing external validation creates an emotional vacuum which will hollow out the possibility of true sight. If all art, whether amateurish or timeless, is ultimately a failure to capture the essence of the ideal, and if the pursuit of that ideal is the only real reward we’ve any right to, then it’s perhaps fair to conclude that success as a writer is merely the privilege to forever fail. Seen in this way, failure is akin to mortality, an indispensable ingredient in framing how we allot our brief time on earth. At first glance, this doesn’t seem like much of a bargain, with its quasi-religious overtones of sacrificing this flesh-and-blood life for some nebulous higher reality, some “ideal” world the writer is tasked with revealing to a passel of skeptical real estate developers. In fact, by way of declaring the poet the true possessor of the world, Emerson writes that others are “only tenants and boarders.” The sorry truth of the writing life, however, is that writers are the ones forever paying rent, while those real estate professionals finagle low-interest home loans.

But before we dismiss The Sage of Concord, consider an early poem by Richard Brautigan, one written well before he hit the big-time. Reading these simple lines now—especially in light of that Trout Fishing in America-inspired manuscript in the library, as well as the Emersonian notion that “thou shalt be known only to thine own”—it seems Brautigan may have intuited the heart of the matter all along, even if the verse is out of sync with life in contemporary America, and even if he later, tragically, lost faith in the words of his own youthful ghost.

Hey! This Is What It’s All About

No publication

No money

No star

No fuck

_______________

A friend came over to the house

a few days ago and read one of my poems.

He came back today and asked to read the

same poem over again. After he finished

reading it, he said, “It makes me want

to write poetry.” (2)

Notes

- See Regent’s of Paris, a novel by yours truly that involves small-town car salesmen in a heated basketball tournament, horsemanship, and a mortuary.

- In the year after I visited The Brautigan Library, both of my books mentioned here were picked up by small publishers. This was lucky, and I’m grateful, but it hasn’t necessarily changed my thoughts on literary failure. In fact, holding my own books in my hands, the above feels truer than ever.