https://cutleafjournal.com/content/does-the-enoree-river-remember-hans-einstein-and-other-poems

October 2022

|

Poetry

|

John Lane

Does The Enoree River Remember Hans Einstein?

Does The Enoree River Remember Hans Einstein?

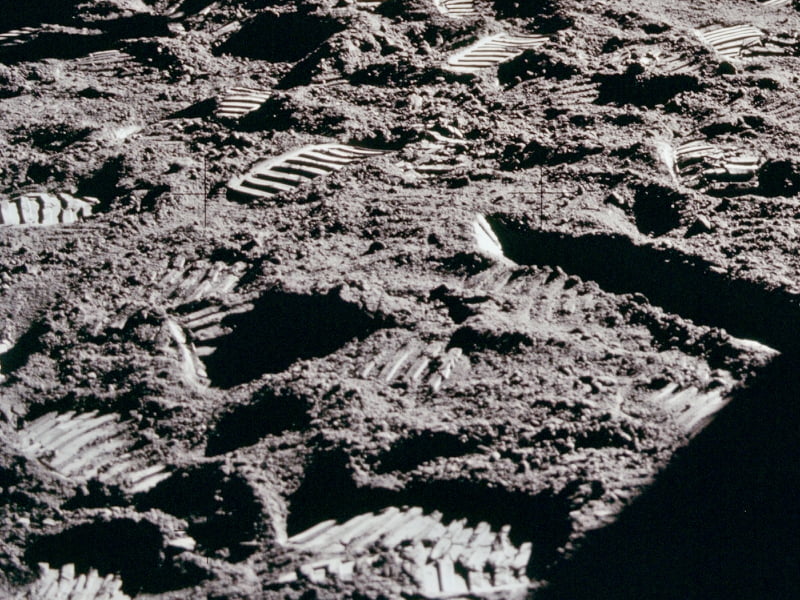

Albert Einstein’s son Hans worked as a hydrologist on a river near Greenville, SC. His research weir is still there in the river but reached only by canoe. —for Dan Richter Ask the scientist and the geopoet in a small green fiberglass canoe pulling over deadfall from two miles upstream to reach this altar to the past. Ask woody debris, carbon storage, wildlife bridges, a deer stampede, perplexed suburbanites lounging on stream side. Ask arrival by self-propulsion to that hidden forgotten spot on the river. Ask Hans Einstein’s lab built in 1930s, a research weir for measuring sediment bed load in the river. Ask Einstein’s aged instrument formed of Depression concrete. Ask the thick river comb, piano keys the river plays for us. Ask the formed shoots the current drains through downstream like a boulder garden. Ask the scientist up to his knees drumming on concrete with his paddle, making wild river jazz. Ask if an argument can be made that sediment is not something to understand. Ask about eighty years measured not in history but in floods and droughts. Ask Einstein’s very artifact— approached by water on a late fall Sunday. Ask Einstein’s concrete Ozymandias cast on gneiss, slick with algae, yet still not yielding. Ask decades of floods. Ask the jet taking off and landing at the nearby airport. Ask poison ivy and greenbriar. Ask the sweetgum snapped by high water somewhere upstream and strung like a bow in current. Ask cedars on the far side, the only green. Ask, hence, the last of fall color. Ask Gibbs Shoals downstream stretching all the way to the Vietnamese Catholic church. Ask the scientist’s tippy canoe still upright like a fallen leaf. Ask the schema we’ve brought along, a ghost of the service to science Einstein performed. Ask his fluvial data stored off-site in the National Archives. Ask the territory. Ask the mystery, these slab fingers laid parallel with slots for some contraption. To control the flow? Ask a flight of doves above.

The Worry-Oak

The storm is a retreating army, foraging our hidden provisions. The worry-oak roots are sodden oatmeal, not nourishing ropes to climb to heaven, not the sinews the worry-oak rides to eternity. The roots snap in least wind but we can’t hear them. Instead we watch the hula dance above our rafters, thinking that is the big show. We gauge the gale of grievances weather pitches at us, mortal and secure in this thimble of human certainty we call a home. That stabbing music? Acorns tap dancing on the roof, bound for a sodden yard where squirrels would mire in our acres if they would abandon their huts of sticks high in the air. They’ve made our mistake, thinking they can sleep it out, nestled among a compost of insulting leaves, heir to what remains every fall of a proud forest, a rainbow so striking that inside thumbtacks hold the scene to our wall in places where trees are now two by fours, ghosts of the beasts that threaten our surety. Dawn is hours away. Rain pulls me from sheets made a nest by wear, but rising is not enough to quell the fear the worry oak outside our window will split our house in two, a sandwich on the yard’s cutting board. First light. I stare up into the dilemma of limbs.