Chris Arthur

Bright Side Blues

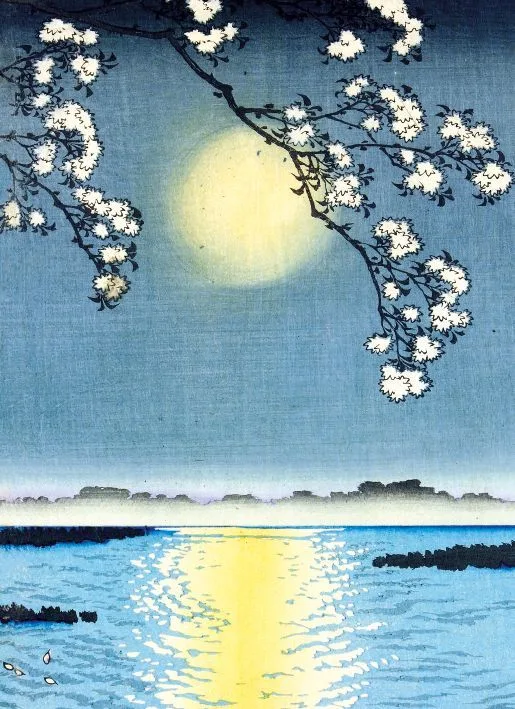

I’d always taken it to be a pleasant picture: behind a spray of cherry branches laden with white blossom, the rising sun – still hazy in an early morning sky – casts golden reflections on the river below it. There’s a band of mist along the far-side riverbank, softly obscuring what looks like thickly wooded countryside behind it. The blue of sky and water, together with the sun’s warming yellow, dominate the scene. The dark of overhanging branches near at hand, echoed by the woods in the distance, provides definition and contrast, whilst the white cherry blossom beckons the eye into this inviting tableau. The lightening that’s evident in the dark blue sky above the band of mist suggests the day is just beginning. There’s no detectable human presence. The picture seems to depict a small cameo of unsullied natural beauty. For a long while that’s how I thought of it: a peacefully Edenic scene with a new day dawning into being.

The notecards that feature this pleasing view, as it’s depicted in a Japanese woodblock print, are from the British Museum. A couple of Christmases ago my daughter, knowing of my liking for Japanese art, gave me a pack of them. I’ve sent these notecards out to various correspondents since then, not realizing that, far from simply showing a pleasant riverine outlook, something altogether less benign is implicit in this scene. Rather than consisting of a single self-contained image that presents the view the artist wished to portray, the notecards feature only one part of what was originally created as a triptych. Seen as a whole, the complete work still has claim to beauty, and there’s no denying the high degree of artistry and technical accomplishment with which it’s worked. Aesthetically, it remains impressive – even when the horror of what it shows becomes clear.

The information on the notecards is sparse. All that’s given is the title – “Sumida River – the Ancient Story of Umewaka” – together with this caption:

Detail from the series Famous Places of the East, 1883. Colour woodblock print by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, Japanese.

There’s also a British Museum serial number and the date when this artwork was acquired, 1906. Like the picture itself, there’s nothing in these details to suggest anything ugly. It’s only when you see the other two panels of the triptych, and find out what Umewaka’s story is about, that what’s shown on the notecards takes on an altogether different resonance.

* * *

The ancient story that Yoshitoshi draws on for his picture tells of how a boy – Umewaka – fell into the hands of slavers and perished. The details of what happened are uncertain. We can’t be sure of Umewaka’s age. He’s often described as being twelve years old, but some accounts suggest he was as young as seven. It’s not clear whether he died from illness and/or exhaustion whilst in the hands of his captors, or if, ailing, they abandoned him to die alone, or if they murdered him. The slave traders are often described as “child sellers,” suggesting they specialized in the abduction, abuse, and sale of minors. It’s hard to tell to what extent the story is based on actual events. One indication of its veracity – or of the fact that people believed it to be true – is the existence of Mokubo-ji, a Buddhist temple built in 977 as a memorial beside what was said to be the site of the boy’s grave. The temple still exists today. Traditionally, the date of Umewaka’s death is given as April 15th and each year on that day the temple holds a special service.

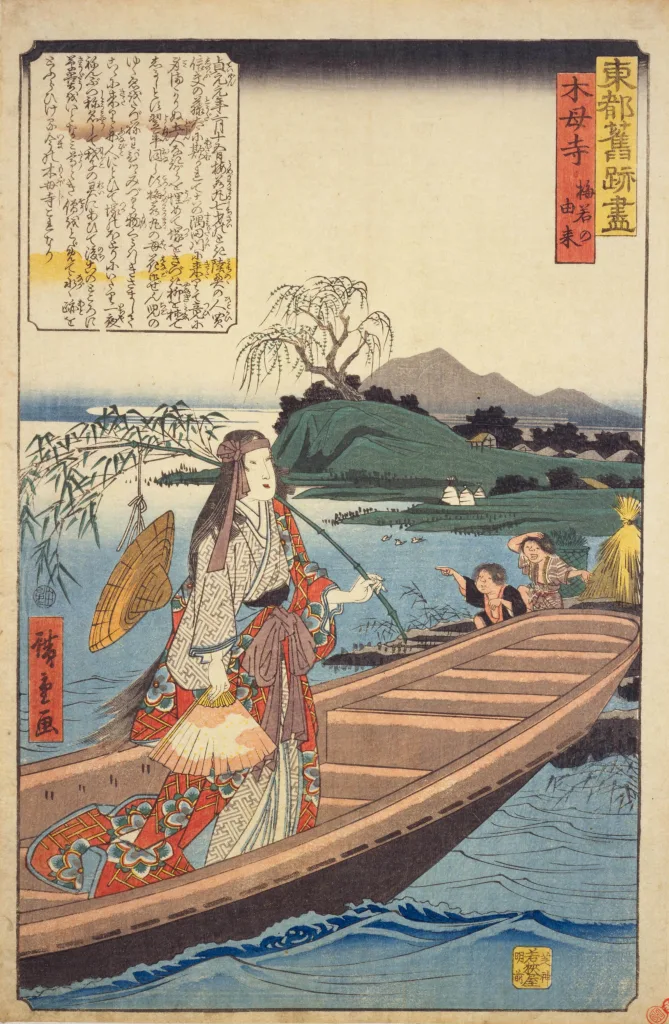

Umewaka’s story is the subject of Sumidagawa (The Sumida River), a fifteenth century Noh play by Kanze Motomasa. In it, the boy’s mother becomes the key character. Her desperate search for her missing child and her despair when she discovers a grave – and briefly encounters what she believes is the ghost of her son – instead of finding a living, breathing boy, are central elements in the drama. It was this Noh play that Benjamin Britten saw on a visit to Japan in 1956. He was inspired by it to compose “Curlew River,” the first of his “Parables for Church Performance.” Unsurprisingly, since it’s such a key feature of the landscape in the area around Edo – which became Tokyo – the Sumida River is a recurring feature in the work of Japan’s two great artists, Hokusai and Hiroshige. One of Hiroshige’s woodblock prints shows Umewaka’s distraught mother being jeered at by children on the riverbank as she drifts past them in a boat, haunting the vicinity where her beloved child met his end. For them, her grief-induced madness has turned her into a figure of ridicule, inviting mockery. They are too young to see the tragedy of her situation.

The middle panel in Yoshitoshi’s triptych shows Umewaka kneeling on the ground. His right arm is thrown up in a protective gesture, and petals of cherry blossom fall all around him. Taken alone, this panel could be viewed simply as the depiction of a strikingly handsome boy portrayed with a common motif of transience in Japanese art, namely cherry blossom. The falling petals provide a visual symbol of life’s passing, emphasizing that his youth and beauty will not last; like the cherry, his bloom will soon fade.

It’s only when the first panel comes into view that this interpretation falters. The man in this section of the triptych is armed and threatening. The aura he carries is one of menace rather than protection. He has the air of an abductor, assailant, jailer, or executioner. This is Tōta, the slaver. With his presence in the picture, Umewaka’s raised arm seems more like an instinctive attempt to ward off an imminent blow than a graceful, if impotent, gesture that seeks to brush away the falling petals of life’s unstoppable ephemerality.

Looking at the three panels – and how viewing them singly and together puts such a different spin on things – makes me think of how the world is presented by the news. Sometimes it feels as if what’s reported is just the bad news, with all the emphasis put on what happens in the first two panels, where misery of one sort or another dominates. The beauty and tranquillity that characterize the third panel are rarely, if ever, mentioned. Putting the news and Yoshitoshi’s triptych into the same cognitive frame was likely prompted by a comment from the daughter who gave me the notecards. She told me recently that she’s stopped watching or listening to news bulletins. They give such an overwhelmingly depressing view of things – and things she feels powerless to remedy – that being kept informed about them seems pointlessly disheartening. Given this strategy for looking (or not looking) at the world, it seems fitting that – albeit unknowingly – she gifted me a set of notecards that promote looking at the bright side – by the simple expedient of omitting scenes that cast shadows on it.

* * *

Descriptions of the triptych commonly refer to it as a masterpiece, an example of Yoshitoshi’s artistry and his virtuosity in the medium of the woodblock print. I don’t disagree with that. What surprises me is that most commentators insist that the third panel is lit not by the sun but by a full moon. Given the yellowness of the light, particularly as it’s reflected on the river’s blue ripples, I’ve always seen it as a sunrise scene, a kind of aubade, a dawn song without words, rich in the promise of a new day. For me, moonlight would be cooler, more distancing, it would rob the scene of its poignant promise of warmth and new beginnings. I’m left wondering if my sun-reading is simply an error, or if – knowing of Yoshitishi’s “One Hundred Aspects of the Moon” – commentators have read things in the light of this justly famous series.

From my perspective, whether it’s the sun or moon doesn’t really matter. Neither the fine detail of the painting and its interpretation, nor the historicity of Umewaka’s story, are my main concern. I’m more interested in the way that seeing the single panel of the triptych, as it’s reproduced on my British Museum notecards, gave me such an erroneous view. Taken by itself, the sun (as I continue to think of it) casts its yellow reflection on the river’s water. This, the blue sky, band of mist, cherry blossom, and distant trees combine to nudge the mind toward some kind of pastoral idyll in its reading of what’s shown. Seen in the context of the other two panels, and with a knowledge of what the story of Umewaka involves, this mood of benign interpretation undergoes a seismic shift. The pastoral scene, innocently empty of humanity, becomes instead a statement of terrible absence, of the emptiness that’s left after a child’s life has been taken. It shows a new day dawning, indifferent to any human emotions. The sun shines equally on children playing along the riverbank, a slaver’s cruelty, a boy’s death, and a mother’s inconsolable grief.

* * *

Although there’s no intentional deception of the kind we’ve grown used to in this age of sophisticated and deliberate disinformation, I still feel like I’ve been tricked. It’s not as if the British Museum set out to deceive me – they simply wanted an appealing image to put on this piece of merchandise. And, aesthetics apart, from a purely practical point of view, a single panel from Yoshitoshi’s triptych fits the dimensions of a notecard more easily than the full thing would. I’m told plainly enough on the card that this is a “detail” from a series – “Famous Places of the East” – a clear signal that what’s given is partial, only a fraction of the whole. Moreover, since the caption includes the phrase “The Ancient Story of Umewaka,” I should have realized that the beautiful sunrise (full moon…) over the river is just the setting in which a story unfolds, rather than the actual narrative itself. The notecard features the background, the set, the mis en scene, it’s not the primary point of interest. All this notwithstanding, in the light of what I now know about the picture, I feel hoodwinked, taken in, as if the wool had been pulled over my eyes and I’d been made the victim of a scam.

As a result, I hesitate to send the notecards now. I know that most recipients would simply see “Sumida River – The Ancient Story of Umewaka” as I used to see it, taking it to be an attractive scene, an example of how visually pleasing Japanese woodblock prints can be. The ugly cargo associated with it is undetectable unless you see all three panels, or know the story that’s associated with Umewaka’s name. But it would feel dishonest to send the notecards now. To do so would be tantamount to continuing a deception, tacitly approving of a kind of censorship where what’s unpleasant is simply sheared away and replaced with a standalone cosmetic version that smooths and gentles life’s jagged edges into the anodyne illusion of a pleasant outlook. Knowing how he died and then simply ignoring Umewaka’s fate, deleting – not including in the picture – the unpleasant parts of the story as Yoshitoshi depicted them – would come uncomfortably close to allowing propaganda to stand unchallenged. It would feel not unlike pretending that the multiple child casualties in Ukraine, Gaza, and other war zones never happened, that the world we live in is a beautiful and peaceful place untroubled by bloodshed, screams, or tears. I understand my daughter’s opting not to watch the news, to determinedly look on the bright side and blot out anything that threatens to rewrite it in a darker hue. But even supposing it was possible to insulate yourself from journalistic gloom, surely filtering out evidence simply on the grounds that you don’t like it is bound to leave you with a perilously unbalanced point of view. Sound judgment relies on looking beyond selective tellings, trying to get an accurate – rather than just an attractive – picture.

* * *

My experience of seeing Yoshitoshi’s complete triptych, after a long period of knowing only a single panel from it, has acted to expose a nerve. It’s no longer just an issue about how one painting should be presented. Instead, thinking about that question has fostered the asking of a much wider one, namely: in what terms should we think of life itself? I know there are a multiplicity of perspectives on such a wide-ranging matter, a whole array of possible standpoints, both naïve and sophisticated, that might be taken. But increasingly my concern has become simplified and pared down. It cuts through the inherent complexities to focus on trying to decide which of two broad currents of interpretation, positive or negative, give a more accurate reading of the river on which all of us are borne from birth to death. I’m reminded of William James’s division of humanity into two fundamental types: what he called the “healthy minded” and “sick souled.” For the former, the river of life is as benign and beautiful as the Sumida River as pictured in the last frame of Yoshitoshi’s triptych. For the latter, it’s as if the cruelty and pain of the two preceding frames have been concentrated into a bitter distillate that seeps its way into all the world’s waterways, souring them with the taste of suffering, hopelessness, and death. The healthy minded see a glass half full with many opportunities and pleasures; they’re optimistic about enjoying life and finding happiness. The sick souled see a glass half empty with the dregs of a toxic draught that has already poisoned them. Their pessimism – which they see as realism – cannot see past the slings and arrows that afflict us and the inevitability of death.

Around the rawness of the nerve that’s been laid bare by encountering the triptych under the circumstances that I did, a cluster of unsettling questions swarms. Is it always better to see the whole picture, rather than just part of it? Why not focus on the beautiful aspects of life? Is there any point in looking at ugliness unless we have to? Do we not encounter enough violence, cruelty, and unpleasantness already without giving it expression in our art? Isn’t it preferable to find a pleasing picture to put on notecards, rather than something upsetting? We all know that innocents are preyed on, that kidnap, persecution, rape, and murder happen. But would it not be perverse to emblazon them on notecards sent to friends? What’s wrong with looking on the bright side, turning away from the things that threaten to dull and besmirch it? Why not concentrate on life’s positives instead of falling victim to the dismal outlook of a sick souled mindset?

On the other hand, would sending out the idyllic sunlit (moonlit…) view, knowing there is more to it, not constitute a kind of trickery? Would I really wish to deceive my correspondents by sending a picture that hides by omission life’s hard realities? But is choosing a benign outlook any worse that choosing an ancient one? After all, the Sumida River that flows through Tokyo today looks profoundly different to the river that met Yoshitoshi’s eyes. In his day, it ran through countryside and was spanned by only a few bridges. Today, the river flows under twenty-six bridges as it makes its way through a densely urbanized cityscape. If I opt for his nineteenth century view, preferring natural surroundings to contemporary glass and concrete, am I any more guilty of deception than I would be if I chose to make no mention of Umewaka and his tragic story? I feel caught between approving of an aesthetically justified excerpting of an image that’s likely to bring pleasure, and disapproving of the way it represents a bowdlerizing of Umewaka’s story; the way considering it in isolation acts to put a smiling mask over the savagery beneath it.

* * *

Sometimes now, I map what Yoshitoshi’s triptych has come to represent onto my own life. I’ve been fortunate enough to have spent time in many beautiful places. I’d have no difficulty finding scenes that, had I Yoshitoshi’s artistic skill, would provide ample raw material for images as pleasant as the third panel’s view of the Sumida River. Thankfully, looking at the first panel, there have been no figures directly comparable to Tōta, Umewaka’s tormentor. Instead, I could populate this section of my triptych with a series of portraits of people who have loved and supported me along life’s way. But of course this isn’t to say there haven’t also been pains and disappointments, worries, terrors, illnesses, fears, people who have caused problems rather than solved them. And all of us, however we fare, are vulnerable to what the clouds of cherry blossom betoken in the second panel. They fall upon us remorselessly – their soft, unnoticed erosion of our days grind us and everything into nothingness. Come looking for us and, in the end, like Umewaka’s mother, the most you’ll find of any of us will be our grave.

I still can’t make up my mind – to put it in terms of Yoshitoshi’s triptych – whether it’s better to see the whole picture, or try to concentrate on the final panel, emptied of humanity’s woes and filled with natural beauty. Is adopting such a partial view just a hiding of one’s head in the sand of wilful ignorance? Or is it a judicious opting to concentrate on what’s uplifting rather than upsetting? As I’ve grown older, felt first panel demons multiply and draw ever closer – albeit not in the same guise as the figure threatening Umewaka – I’ve become more accepting of the – spurious? – comfort offered by a partial view. We all know life’s no bed of roses, there are thorns aplenty and everyone is impaled on the inexorable barb of their own mortality. Under such grim circumstances it’s surely understandable why we might simply want to turn our heads and look the other way, even if such looking on the bright side is as much self-deception as it is perception. A trace of passing bliss – however dubious its foundations – may be preferable to misery and truth.

Although I’ve come to think of positive and negative views of life in terms of seeing Yoshitoshi’s triptych in whole or part, and sometimes read my own experience and outlook according to the emphases given by looking at the different panels, I know the parallel between this artwork and life as a whole is strained at best. With Yoshitoshi’s triptych it’s possible to see it in its entirety; with life it’s not. We’re only ever cognizant of a tiny fraction of existence. It’s as if we’re specks of sentience in the corner of one section of a maybe infinitely extensive multi-panel work. There’s room enough to alternate between healthy minded and sick souled perspectives according to how life’s moments strike us in all their unpredictable variety – a both/and rather than an either/or approach. I find that at once comforting and daunting. Comforting in that, never having the full picture, any worldview we take, whether positive or negative, is bound to be provisional and incomplete – which means we’re never trapped in it. The possibility of another view always remains open. To imagine otherwise would be to abandon the humility our ignorance ought to breed. Such lack of certainty about where we stand is also daunting in that it’s a reminder of scales of time and space that dwarf our individual existences into seemingly annihilating insignificance. Think of all the cherry blossom there has ever been, a blizzard of petals falling with the gentlest of impacts on the earth. There are more panels in the astonishing polyptych of being than if each petal unfolded into its own three-part woodblock masterpiece.