Margo Isidora Katz

The Last Baby

It was a miracle really that I got pregnant the third time. I got pregnant the first time because my mother, saddled with two daughters who married in their mid-thirties, wanted grandchildren. The first pregnancy ended in the first trimester with sudden, heavy bleeding in the middle of the night; a run-of-the-mill miscarriage. I called the obstetrician. “Put on a pad,” she said, irritated. “This is beyond pad,” I replied.

It took fifteen minutes to drive to the Santa Monica Hospital Emergency Room. Two rolls of paper towels, jammed between my legs, were saturated by the time we arrived. Behind privacy curtains in the exam room, I bled out indistinguishable parts of the baby. An ultrasound revealed an empty uterus and the surgeon was called to perform an emergent D&C. I woke to the plunk-plunk-plunk of the ice machine where they had stashed my bed in the overcrowded maternity ward. I called Jessica. She called our parents. The first grandchild was gone. Spilled on the floor of the emergency room.

Later that night Jessica came to me with flowers in hand and tears in her eyes. Instead of crying, I worried that the miscarriage portended a lifetime of infertility. “At least,” my mother reminded me, “you know you can get pregnant.”

She was right. My second pregnancy and first baby was Daisy Mae, born in 2001 in the Steven Spielberg and Amy Irving Birthing Room at Santa Monica Hospital. The irony of this was not lost on me; 11 years earlier, new to Los Angeles as a screenwriting fellow at Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment, I had sweated profusely upon meeting the great director. The rivulets of perspiration that saturated the waistband of my underpants were nothing compared to the Amityville horror I left in my wake in his Santa Monica Hospital birthing room. In both cases, Steven Spielberg wouldn’t have known me if he had tripped over me.

The years passed. We moved to Rhode Island and lived hand to mouth. The marriage was unhappy and unstable, but I was the eldest of two children and that was the configuration I knew and wanted.

Daisy was the only only-child in nursery school. That, and being ten years older than all the other parents, made me self-conscious. I was tortured by the thought of Daisy standing alone at my grave, yet having a second child lingered on my to-do list, after painting the bathroom and doing my taxes. The day four-year-old Daisy asked, “Why am I the only one who doesn’t have a brother or sister to love me?” was the day I became wildly and willfully determined to have that second child no matter the cost or consequence.

I was 45 when I got pregnant the third time. With relief, I envisioned Daisy standing with her younger sibling at my grave. My age alone made the pregnancy high-risk. But what does risk mean when you really want something? The first genetic test revealed a 22-percent risk. But risk of what? The list was long. I ignored it. An amniocentesis was scheduled. Afterwards, on the narrow street outside the doctor’s office I found a parking ticket on the windshield of my car. I got in the car and started the engine. I was shaking so violently I couldn’t drive. The window of time between the amniocentesis and the results is unbearable. With Daisy, we got the news under November skies on the east end of Long Island. She was a girl and she was fine. We wept with relief. This time, the call came to me at my office under harsh fluorescent lights. It was not the tone of the doctor’s voice that tipped me off, but the hesitation before she said, “I have some bad news.” I don’t know what sound emerged from me, but I had never heard it before.

The doctor gave me the facts: Trisomy 18, also known as Edwards syndrome, is a genetic disorder in which the fetus has three copies of chromosome 18 instead of the usual two. Unlike Down Syndrome, caused by a complete or partial Trisomy 21, Trisomy 18 babies are usually stillborn. Most born alive die soon after birth. Those that manage to live longer have significant and profound physical and developmental deficits.

“Are you sure?” I asked. “Are you positive?”

“These are the preliminary results. The final results take ten days.”

Even with the facts, I couldn’t digest the decision in front of me. I had argued and voted pro-choice my entire life, yet my personal badge of honor was that I had never had an abortion. It was all theoretical before now. Faced with the actual decision, I was rudderless.

“What would you do, Doctor?” I asked. What would you do if within you lay the horror you’re describing… the wolfman of babies?

“I would terminate the pregnancy,” she said. “It’s your decision, but if I were in your shoes, that’s what I would do.” There was a pause. “If you do decide to terminate, we need to schedule you today. There are only two doctors in the state who will do a second trimester D&E.”

I hung up the phone and called my husband. Maddeningly unreliable in times of crisis or decision-making, and skilled in trivial words of comfort, I got from him exactly what I expected. I called my mother. If the noise I made earlier was foreign to me, the strangled cry of grief that came from her was unbearable. “You can’t have it,” she said. “There is no quality of life in that kind of disability. Who knows how long it will live. You may have to take care of it for the rest of your life. Or Daisy for the rest of hers. The costs will be insurmountable.”

“How can I do something like this to my baby?” I asked.

“It’s not a baby,” she admonished, “it’s a fetus.”

When I called the doctor back, I asked two things of her: please don’t let it suffer and please don’t make me labor. The D&E – E for evacuation – was booked for St. Patrick’s Day. The website for the Trisomy 18 Foundation claimed to offer validation and support for parents going through this particular experience. Yet there were no testimonials from those who decided to terminate. Instead, there were upbeat stories of doomed pregnancies and photographs of families cradling mangled or stillborn babies.

What joy I had felt when Daisy moved within me. She teased me with her butterfly turns and tickles, rolled within me like a prideful tide. Proof of life. I couldn’t wait to meet her. Now, I was pregnant with an execution date and I was the executioner. I lay in bed at night and prayed I wouldn’t feel the baby kick. I tried to distance myself from the life churning inside me, turning my head from the gruesome accident in my belly. I didn’t want to fall in love with something I was going to kill.

I decided I would have the baby during one of my daily cry-and-drives through Providence. It was an epiphany, a lightning bolt of clarity; I needed to experience the agony of giving birth to a dead or dying child. This was my purpose, I reasoned. I would be transformed from murderer to saint. My ever-practical mother talked me off that ledge when I told her of my decision. “That’s ridiculous,” she said, pulling me back from my plummet into insanity. “No one needs to experience the death of a child.”

The sun was rising on March 18th when we entered Women & Infants Hospital. I shared a revolving door with a young woman in the early throes of labor. She would leave with a baby. I would leave empty-handed. Not everybody gets a prize.

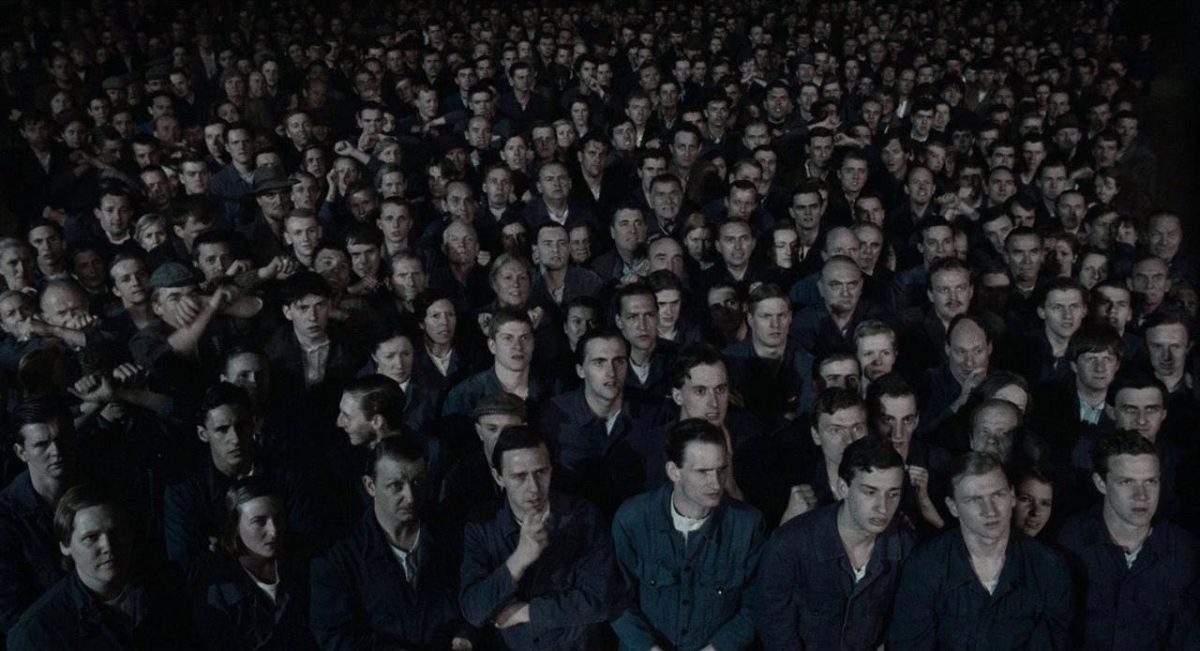

I obediently changed into a gown. They showed me to a stretcher in a harshly-lit Orwellian pre-op room with 12 empty beds. My husband sat with me, running interference with empty small talk. His specialty. It was cold and they gave me a warm blanket. I lost all track of time. As one does when waiting, I leafed mindlessly through People magazine. The cover story about an astronaut love triangle was a distraction but the story about Patrick Dempsey having twins shocked me back into where I was and why. This was a different kind of waiting room. I looked down and noticed the swell of my abdomen clearly outlined under the blanket. I was stunned to realize how pregnant I actually looked.

The nurse put an IV into my right arm. The saline coursed through my veins. I slept briefly. But didn’t dream. An hour or so later, she hung another bag on the pole. Within moments I felt the first subtle, yet unmistakable wave of an induced contraction. With the contraction came a chill that sent me trembling. Was it from betrayal? The disaster that was unfolding in the isolated darkness of my body had taken another tragic turn. My Titanic. The nurse brought another blanket and tucked it gently around me as if I were a child. She put her hand on my arm.

“This must be very difficult,” she said. The shivering shook my tears loose from their mooring. Not in the privacy of my daily driving weep-fests, but here in a brightly-lit room witnessed by a kind stranger. I turned my head but there was nowhere to hide. Contractions and sobs wracked my body. Even my tears were cold.

It took thirty minutes. When I woke up, I felt like a new woman. Free of my shipwreck and paddling to shore. As I dressed, the nurse had an after-thought.

“Oh, we should have called the social worker. I think there’s a support group.” She rifled through a desk drawer and handed me a card threaded with a slice of sheer, white ribbon. Hanging from the ribbon was a tiny, silver-plated baby bootie. And written on the card: Not far away, in a place close to your heart, a little soul watches over you and whispers: Do not grieve for what might have been, you gave me being and I am – you are my parents forever.

The nurse wheeled me through the hospital lobby to the waiting car. I kept my head down, my eyes averted. I didn’t leave the house for a week. I called the phone number for the support group on the back of the card but the phone had been disconnected. I knew what I had done was right for me, but I felt the shame of failure. When I returned to work, I expected to be righteously snubbed by a physician friend who was a devout Catholic. Instead, she offered me profound compassion and empathy. I felt as if I was made of glass, ready to shatter at each well- intentioned inquiry. When my aunt called to gingerly tell me my cousin was pregnant, I said, “That’s wonderful,” while biting my finger so hard it bled.

One of my first forays out of the house was the unavoidable follow-up appointment. I sat, unpregnant, in the same waiting room where I had waited for the amniocentesis. It was filled with every possible iteration of pregnancy, from the slight swell of the second trimester to third trimester tsunamis; ripe bellies filled to the brim with thriving fetuses who had passed their amniocenteses with flying colors. They mocked me; the woman who waited too long to get pregnant, then gambled, then left the hospital with nothing.

In the exam room there was no need for the paper gown, the exam table, the stirrups. I sat fully-clothed in a chair meant for fathers and partners. The doctor sat opposite me, her face telegraphing… was it pity? How was I feeling? Okay. Any bleeding? No. Pain? None. She rifled through my chart looking for something.

“Ah, here it is.” She fell silent as her eyes scanned the page. “There were hand and foot deformities,” she said, choosing her words carefully.

“What was it?” I used the rest of the air in my lungs to finish the question. “A boy or a girl?”

Her answer, I did not hear. Or maybe I did and chose to forget.

In the ensuing time, when I eventually told the story of my third pregnancy, I would say that it had been a girl and her name would have been Fiona. Seventeen years later, I discovered I had lived with a false memory of her answer. The truth, it turns out, was stashed in a box in the back of a closet. Sandwiched discreetly between a preschool report (Today we colored and glued a penguin. Great day!) and a birthday card (50 looks good on you!) the pathology report was folded in half and three pages long:

Date of delivery: 3/18/2007.

Then: Date of postmortem examination: 3/19/2007.

Then: Contracture hand abnormality (clenched fists with 1st and 2nd digits overlapping 3rd and 4th). The left foot shows outward deviation of the toes.

Then: Clinical history of advanced maternal age and induction for trisomy 18. And finally: Male fetus at 17 weeks gestation according to clinical estimates.

Not Fiona. Not a girl. Mine but not mine. Not watching over me from a distant place. Not a miscarriage or a “lost” pregnancy. Not standing with Daisy Mae at my gravesite.

The afternoon of my abortion, six-year-old Daisy bounded into my bedroom. This old soul (who once saw a photograph of Anne Frank and asked, “Mommy, is she dead?”) saw me and stopped as if she had run into a brick wall. I had rehearsed this for hours but still my voice caught at the sight of her.

“I have some bad news,” I said as I lifted her up to sit with me. “The baby inside my belly was sick and couldn’t get better…” I didn’t have to continue. Her face crumpled. She leaned into me and I wrapped my arms around my last baby.