Alan Michael Parker

The Edge of the World

Here’s a drawing: Fig. 1.

What is it?

I offer this drawing to begin a conversation about what we see: it’s a cartoon without a caption, focusing us upon the visual elements, and thus asking for formal analysis. So that’s where we’ll start, by saying what we see. Which is where I think the mind goes first, when encountering a cartoon, into “What’s that?”

For a number of reasons—some art historical, some perceptual, and all very much worth investigating—the louche rectangle drawn here may be read as a frame. Arguably, the reader assumes the world inside the rectangle-frame to be different from the world outside the rectangle-frame; in fact, we might even assume that the space outside to be “our” world, sharing reality with the reader. Around the frame, the page itself—that’s part of what we know, and where we live. By which I mean here in North Carolina, for me, but also everywhere else, because I exist in so many virtual ways, as do we all these days. And it’s in those ways that the rules are different, and not just for cartoonists, of which I am one.

Is the Internet a frame? Consider how many ways the answer’s “yes.”

What is a frame? A a phone, or on a laptop, an image projected in a classroom, these are self-contained technologies bordered by an outside world. In other words, framed. And that, my friend, makes cartooning even more important.

So let’s talk about the cartoon on the page, for now. Next, the first drawing gets a caption: Fig. 2.

With this caption, the circle and the half-circle are now in a relationship. Whether we read the half-circle as attempting to flee the full circle and trying to exit the frame, or entering the frame but separated from the full circle, the space between the two “characters” is now rendered as the problem that defines their relationship. They aren’t together; someone has “commitment issues.” What was partially implied in Fig.1 –the same drawing, but no caption—is now named. The caption names the relationship between the circle and half-circle; the space between them reads as a symbol.

So let’s try another caption: Fig. 3.

With this second caption, we’ve reversed the magnetic poles of the narrative. Now the two characters want to be together, but the space between them doesn’t allow for connection, their desires thwarted by the composition. And we project ourselves into that yearning because we implicitly understand physical distance as emotional separation. Just think of the long life of postcards, and Wish You Were Here.

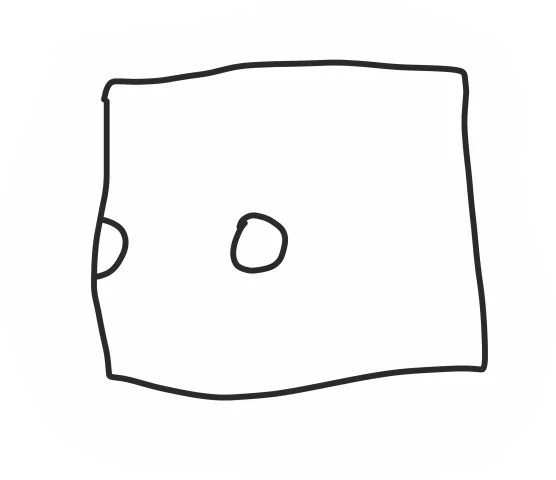

Consider a third version: Fig. 4.

could see the edge of the world

Here, we’ve anthropomorphized the frame itself, the full circle and half circle depicted as two eyes on a face, the drawing on the page invoking the idea of a character in the world that is the page. But that world has an “edge,” so says the caption—which implies that the world of the page is the world Square Girl occupies exclusively. Because that page isn’t our world anymore; because we know (well, most of us do, aside from the occasional politician or basketball player who can’t win in Boston) that the Earth isn’t flat.

There’s irony here: Square Girl’s search for meaning resembles our own, and we may well project our existential anxiety upon her expression, but we hold her world in our mind. Square Girl’s looking to her right, and thus our left: something’s over there that isn’t part of where we are now. We’re outside her world, and free—or free-ish, depending upon your faithview. Certainly, we’re free enough to turn the page: of course, the page as a frame lasts as long as our attention. Now we go digital. Let’s think for a moment about the difference between “Looking hard to her right, Square Girl could see the edge of the world” viewed as a page in a book versus viewed on a phone. Open the image Full Screen: the phone becomes the frame. The phone in the hand, the hand a part of the body, the phone as the body—lots of Digital Studies people have talked about this issue, including the delightful Allucquère Rosanne Stone, in The War of Desire and Technology at the Close of the Mechanical Age. Consider that bodies and phones die differently; these days, dogs live longer than phones. The cartoon on the phone has the prospect of existing in its form as part of our bodies, cyborgian; “Commitment Issues” implicates our bodies in the digitally consumed artifact.

Let’s try an experiment. Google “single-panel cartoon” and click through a bunch of pages. Google “one panel cartoon” and do the same. Find a cartoonist on Instagram or TikTok, and Like what they do. Let’s see what drops into your Reels over the next few days, or your ads—let’s see what the algorithms think of you after you start chasing different ideas digitally. Didn’t the future just change? That’s actually a cool thing about the Internet: it tells us a little about the future. Which of course lots of people don’t like because the future seems as constrained as it is determined, and increasingly so with AI prominently deployed. Or weaponized? That’s the concern, unnaturally.

Back to cool things: here’s another, different idea. What if the caption of “Looking hard to her right, Square Girl could see the edge of the world” were altered to read “Looking hard to her right, Square Girl could see the Edge of the World”? Now she’s looking at at title, or a multiverse; maybe someone’s reading a book called The Edge of the World. Let’s try another option, “Looking hard to her right, Square Girl could see the Edge of the world”—now I’ve capitalized one letter, and created a proper noun; there’s a place called the Edge, and we’ve situated Square Girl in a speculative environment. See what the tiniest tinies of textual play can do, too? That’s the other part of the cartoon deserving our attention, how image and text as individual types of meaning-making combine to form the work of art, and how nuanced that artwork can be, in part as a result of its minimalism.

To talk about the single panel cartoon in this way is to invoke comics, and their reliance upon “double literacy.” By no means are these ideas mine, or new: Ivan Brunetti, Lynda Barry, and Scott McCloud have all explored fruitfully in charming and substantive ways how comics work, including webcomics. (In Brunetti’s case, those considerations come fraught with occasional ethical missteps and egregious slurs). And others, such as Neil Cohn, have explored the neurological response we have to the codes present in comics, and their reapportioning of meaning in terms of linguistics. Still others have traced the cultural history of comics, or imagined—as Michael Chabon does—the fictional lives of comics creators. But there’s always more to be said, and the unsaid needs to be named, since almost all of the best books on graphic narratives are based on the study of print comics.

But now that we have memes, and Instagram, and the brush tool, the principles of comics don’t stretch enough: that rubber band breaks. The cartoon on the Internet is ubiquitous: the single-panel cartoon on the Internet is more and more a genre, and needs its interpreters too, people who see the cartoon on the Internet as a distinct idea, relevant rather than a threat to print culture. Because the Internet is also who we think we are.

Let’s keep going with our formal understanding. To complicate the situation of Square Girl’s quest, as well as the questions we’re beginning to ask, here’s another drawing: Fig. 5.

could see the edge of the world

Now where’s Square Girl’s world? Is it the drawn laptop’s screen? That seems unlikely. Does it begin or end at the edge of the laptop? If so, then we may well be back in the world with her, or at least in a world that has the same parameters as hers. The drawing may well be of our laptop—and even if it isn’t, we now exist in a world we know, with laptops (that might be viewed on phones). Nonetheless, we also know that the drawing’s a drawing, the materiality of the imagery more present as a result of the recognizable, simply rendered objects depicted. Clearly, we’re looking at a drawing, which means it’s not “real,” right? So our world and her world are both made up, somehow.

Now what if Fig. 5 were viewed on a smart phone by a reader riding to work on a subway car? And that reader pinches the image to fill the smart phone screen? Or doesn’t quite, and there’s space between the image and the contours of the phone—and if we capitalize Edge in that case, wouldn’t there now be a world between the cartoon… and the phone itself, some unidentified space on the screen (but not)? Push the ideas further: what if there are LED announcements flashing above the subway car’s windows, newly digitized ads for a film, yet again ripped off from and but not quite identical to the opening credits of Blade Runner? How many digital universes are there, or virtual places that we occupy?

While I’m not trying to over-complicate this notion of the real and the virtual, or run screaming in fear as AI rewrites us, or Late-Stage Capitalism redefines us, virtual existence has changed physical existence, which means virtual existence has also changed cartoons. Given that a cartoon always has a frame—drawn, or otherwise implied; the page itself, the screen, the book—the interplay between the virtual and the walking-around-life seems especially bouncy when thinking about the single-page cartoon.

The Internet is no longer distinct from walking-around-life, or our interactions with each other: we see couples part ways on the street by giving each other a thumbs-up Like. Now, when we talk about “digital culture,” we’re no longer exclusively discussing bytes, or parameters, or Chat GPT or Claude; just as when we talk about cartoons or comics we’re no longer exclusively thinking of the Funnies, or The Simpsons or Nancy or Adult Swim. All of which means that virtual and the walking-around-worlds interpellate one another: our identities express both virtual and walking-around power dynamics, as do our cartoons. As I write this on my laptop, I’m simultaneously logged into twenty or so websites, with my money, my employment benefits, my memories, and my future purchases in a saved shopping cart all one-clickable. I change what I want simply by liking something; the algorithm becomes me. “Online” doesn’t exist now that we’re always online.

Let’s return to the notion of double literacy, and the relationship between image and text, and the very human search for meaning. Here’s the same drawing as above, with a new caption: Fig. 6.

in the flower vase

We’re back to a world of observing, and the act of inferring. Because a good cartoon asks us to infer—to fill in the missing information, complete the sentence, figure out the unsaid. A cartoon exists in two literacies, image and text, and each activates the other, requiring the other as an act of completion. Such inferring in a graphic novel or sequential narrative occurs within each frame but also between the frames, or “panels”; it’s a process Scott McCloud writes about beautifully in Understanding Comics, the idea of “closure,” and how the reader understands what happens between the panels, in what’s called the “gutter.”

By contrast, here I’m exploring the single-panel cartoon—or so-called “gag cartoon,” a term born of the caption-as-punchline, dating back to the funny pages. (Think The Far Side rather than Peanuts.) In this kind of cartoon the process of inferring occurs in the reader’s understanding bouncing back and forth between image and text, each enlarging our comprehension of the other, no other formal elements available. (Which is why I said “bouncy” earlier.) In the cartoon, most importantly for us and this argument, there isn’t a next panel, and no space between panels for other meanings: there’s only what’s around the cartoon, our bodies, our frames, and the Internet.

Here’s something I love: because it’s a cartoon, a magic key exists.

Here’s something else I love: the reader gets to infer the actions (before and after) of the characters, the character’s world built by the reader’s bouncing between literacies, image and text. But actions assume a past and a future, too.

Here’s another something else I love: the drawing’s simple, the language accessible, and together, the caption and the image require an act of imagination far beyond the simplicity of the two parts. 1 + 1 = 3.

But the math offered above seems an exaggeration, alas. In Fig. 6, there isn’t much content in the drawing. We see what we see, the objects—flower, vase, laptop, table—all recognizable, but also boring. The best part of the image is Square Girl and her expression, but even that would benefit from another panel to be elucidated fully, the single-panel less self-contained, the story not over. In that sense, the single panel here doesn’t do its job, since it needs another panel, and for us to turn a page or hit the Continue arrow.

Moreover, the drawing has limited visual appeal aside from some slight charm to its crude rendering, and while we understand it’s a drawing by virtue of the simple lines, that’s all: the drawing does nothing visually to excite our interest, or to help us understand. There’s no insight in the drawing, limited content in the artwork, and almost no imagination in its rendering. As such, I would argue, this is not a good cartoon: the caption does too much of the work. In effect, instead of 1 + 1 = 3, the cartoon is more like 1/3 + 1 = 2. That’s not good enough. So let’s try adding something that has visual appeal: Fig. 7.

in the flower vase

Oh my gosh, what’s that? Now Circle Boy is clearly our new main character, this baby-ish monster, given the disc-shaped appendages and circular head-shape of the figure. He’s weird: we look. With the addition of Circle Boy the monster, the cartoon has increased visual interest, the cute monster a protagonist, and someone to care about, and the narrative has become more literary, the principles of storytelling more evident (plot, character, setting, etc.).

But while the monster is cute, and perhaps someone/something with which to identify, the overall cartoon is diminished. Because now the prospect of Square Girl being a character in the frame on the laptop screen has been eliminated. The reader is no longer able to infer actively what the character’s up to, and the cartoon’s been reduced to being an illustrated story (and again, one that requires additional panels to be completed). Ironically, adding the character of Circle Boy Baby Monster to the image has reduced the caption’s value, and trivialized most of what I liked in the previous cartoon, Fig.6., rendering unimportant the inclusion of the laptop, not to mention having eliminated the possibility of Square Girl as a character. We’ve gotten cuter, but not better.

Which brings me back to Fig. 4.

could see the edge of the world

This one’s the best cartoon of the figures presented thus far, but still not great. Why? Once again, because Fig. 4 seems to need other panels to explain the story; Fig. 4 is more of an excerpt from a sequential graphic narrative than a gag cartoon. We want to know what happens next, Square Girl apparently about to begin a quest. Time is a question here, not an answer. Space is the punchline, and that’s not especially funny, or enough.

Also, once we get the whimsical joke that the half-circle and full circle are Square Girl’s eyes, there’s no other visual interest to be found in the drawing. Sure, the edge of the page being the edge of Square Girl’s world is a cool idea, and the Aha! when we realized that the whole drawing is Square Girl has charm, but neither image nor text enlarges upon the other’s meanings.

What I’ve been hoping to argue here is that unlike in a sequential narrative, adding details to a single-panel cartoon tends to increase exponentially the demands placed on the relationship between the image and the text. (And we’re not yet talking about color, of course, which matters.) In a medium dependent upon double literacy, every element added has to mean a couple of different ways. Conversely, simple doesn’t equal great, if there’s not enough content in either the image or the text.

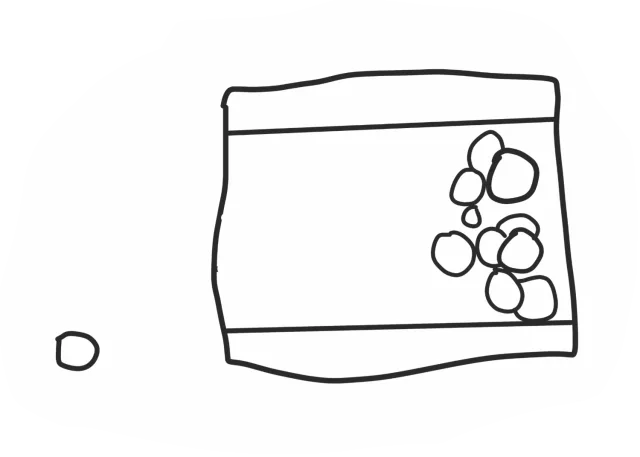

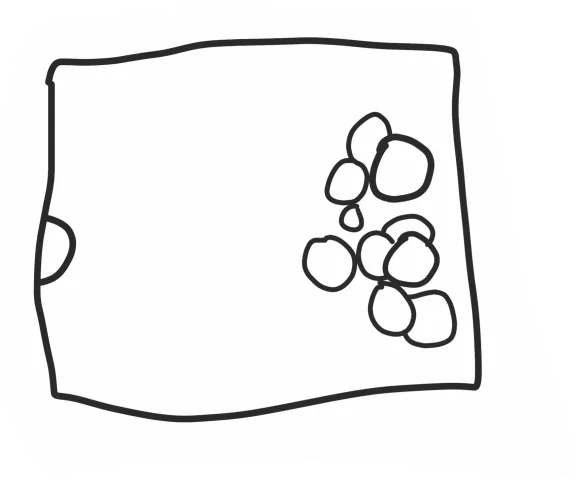

Here’s a wholly different cartoon, with what we’ve learned in mind: Fig. 8.

Let’s start with formal analysis once again, and say what we see:

- A partial circle faces a group of circles.

- The circles are misshapen.

- Some of the circles seem to be on top of one another, creating volumetric space; we are looking from above, or at an image on a screen.

- Count them up: there are 10 circles on the right, plus the half-circle on the left.

- One of the circles is significantly smaller than the others.

- The other 10 circles seem divided slightly, into two groups.

Here’s what we infer:

- The partial circle is Ernie. Each circle has had or will have a turn knocking over one another.

- Their individuality gives them character, not fully anthropomorphized, but close.

- 10 circles = 10 pins, and Ernie’s going to be the bowling ball, and they’re going to knock into them.

- One of the circles is … a child?

- Are the circles afraid? Are they going to save the child circle? Sacrifice it?

Here are questions based on these inferences, as well as leaps of logic based on our reading of image and text, i.e. additional levels of thinking:

- How does a bowling ball knock down other bowling balls?

- What’s the scoring system here?

- Is this how Fate works? Is the word “turn” in the caption a comment upon Fate?

- Here’s a world in which things take turns knocking things. How is this like/unlike my world?

- Who or what is propelling Ernie? The cartoonist? The reader? Who’s the villain?

- Does Ernie mind? Is Ernie happy? Worried?

- I want to see what happens: am I rubber-necking?

- Is there herd behavior here, exposing the little one to peril to save everyone else? Survival of the fittest? Cowardice? Pragmatism?

So, the cartoon’s good, yes? Because whether or not we actively infer all of the available results, or ask each of these questions—or add our own additional observations, inferences, and questions—the image and the text prove individually interesting. When combined, they become more so, 1 + 1 = 3.

An emotional connection has been made, feelings have been invested in the child-ball-thing that might imperiled, and in the ball-people who might be afraid. We become concerned for Ernie, who seems to have been selected to do damage to his ball-people, or simply to be next up in a bowler’s version of The Hunger Games. In these concerns, there’s commentary on the social contract and political theory, on violence and mercy, on the individual’s ethical responsibilities. In the Nth degree of inferring, Ernie may well need to make a personal decision about political action: the cartoon potentially provides a bit of political theatre, in this reading, with a hint of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Do the Right Thing, as well as The Trolley Problem.

For the reader, the stakes are high ethically—but there’s more, because we also collaborate with the mind of the artist. When we participate in a world being built in this way, the artist and the viewer become real, brought into being by each other. In a sense, since the demands of the cartoon assume a human reader, by placing the reader in a relationship that requires the exercise of their individuated consciousness, they’re made present. Arguably, the cartoon creates us.

One more reading, which might be a projection or merely hopeful: maybe Ernie’s trying not to bowl over their ball-friends, and that’s why we only see part of them—they’re attempting to flee the frame by exiting stage right. Maybe they’re trying not to do wrong.

And maybe the frame’s the “real world,” and maybe we’re virtual. And maybe that doesn’t matter anymore, because we’re about to share a good cartoon, and empathize, and have all of the other feelings.

So here’s a final cartoon that but adds possible meanings, the cartoon more simple and complex, somehow, Ernie with some agency.

Read it with me. Read it on your phone, and I’ll read it on mine. Let’s make a world.

Fig. 9: